Everyone should know that the industrial society we live in depends on access to plentiful, convenient, cheap energy – the last two hundred years of rapid economic growth has been underpinned by the large scale use of fossil fuels. And everyone should know that the effect of burning those fossil fuels has been to markedly increase the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere, resulting in a changing climate, with potentially dangerous but still uncertain consequences. But a transition from fossil fuels to low carbon sources of energy isn’t going to take place quickly; existing low carbon energy sources are expensive and difficult to scale up. So rather than pushing on with the politically difficult, slow and expensive business of deploying current low carbon energy sources, why don’t we wait until technology brings us a new generation of cheaper and more scalable low carbon energy? Presumably, one might think, since we’ve known about these issues for some time, we’ve been spending the last twenty years energetically doing research into new energy technologies?

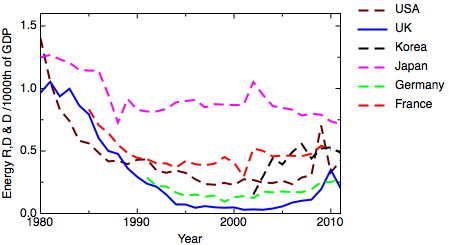

Alas, no. As my graph shows, the decade from 1980 saw a worldwide decline in the fraction of GDP major industrial countries devoted to government funded energy research, development, and demonstration, with only Japan sustaining anything like its earlier intensity of energy research into the 1990s. It was only in the second half of the decade after 2000 that we began to see a recovery, though in the UK and the USA a rapid upturn following the 2007 financial crisis has fallen away again. A rapid post-2000 growth of energy RD&D in Korea is an exception to the general picture. There’s a good discussion of the situation in the USA in a paper by Kamman and Nemet – Reversing the incredible shrinking energy R&D budget. But the largest fall by far was in the UK, where at its low point, the fraction of national resource devoted to energy RD&D fell, in 2003, to an astonishing 0.2% of its value at the 1981 high point.

What’s the story behind these numbers? This can be illustrated by a few key dates. By 1986, a major wind-down of the UK’s program in civil nuclear power was taking place, and the Atomic Energy Authority, the UK government agency responsible for research into civil nuclear power, was made into a “trading fund”, in preparation for privatisation. AEA Technology Ltd was duly floated in 1996, with a rump of the UK Atomic Energy Authority left to decommission nuclear legacy sites and manage the UK’s participation in international fusion research. The privatised AEA Technology attempted to make its way as an energy and environmental consultancy, but the company finally went into liquidation last month, with its assets subsequently being acquired by the engineering company Ricardo. In 1981 civil nuclear power accounted for 68% of the energy R&D budget, so the winding down of this program accounts for a substantial fraction of the loss of energy R&D – but not, as we shall see, all of it.

The definitive story of the UK’s civil nuclear program has yet to be written. That story will include some engineering brilliance, some dismal economics, and an expensive and dangerous legacy of waste and decommissioning, many of whose most undesirable features reflect a deeply entangled relationship with the nuclear weapons program. The run-down of civil nuclear research will have been welcomed by an unlikely alliance of free-marketeers and green campaigners. But now we’re in a situation where even some environmental campaigners are thinking that, if we are to have any hope of limiting climate change, we’ll need nuclear power. From a national perspective this means that this technology will need to be imported. And, because the slow-down in civil nuclear power research has been global, the only technologies that are currently available are essentially incremental upgrades of 1970’s designs.

But even in the 1970’s and 1980’s, nuclear research wasn’t the only energy research going on. In 1983 non-nuclear research and development was £104 million, 34% of the total. By 2001 spending on non-nuclear energy research had declined to £16 million in cash terms (another £15 million was spent on what was left of the nuclear program, including the UK contribution to the Joint European Torus, an international fusion energy research project based in the UK). This is an astonishingly small number, given that the turnover of the UK energy industry at the time accounted for abut 2% of GDP (excluding oil and gas extraction), and given the central importance of energy to a modern economy.

To explain this remarkable decline, we need another date – in 1990 the UK’s electricity industry was privatised, resulting in ten years of corporate reorganisations. The full story is related in Dieter Helm’s book Energy, the State and the Market: British Energy Policy since 1979, but there’s a very readable account in this recent article by James Meek – How we happened to sell off our electricity. In brief, the interests who acquired this national infrastructure found it more profitable to use financial engineering to extract cash from these assets than to invest in them, particularly if those investments – such as research and development – were long term in nature. The government, meanwhile, believed that the magic of a competitive market was the best way of ensuring the long-term security of energy supplies. As the mergers and acquisitions played out, by 2002 most of the UK’s electricity industry was in the hands of vertically integrated European companies like E.on, RWE and EDF (the latter of course being controlled by the French state). In 1994, in the privatised utility sector as a whole (comprising electricity, gas and water supply), £170 million was spent on R&D but by 2005 the total industry spend on R&D in the UK, again across the whole utility sector, was down to £15 million.

By 2005, a recognition was growing in the UK government that the extremely low level of R&D effort in energy – both by government and in industry – might not be a good idea. It is probably fair to associate this change to a single individual, Sir David King, who became the UK Government’s Chief Scientific Advisor in 2000. King was an outspoken and effective advocate about the dangers of climate change, and the need for more research into energy, and as a result there was a significant rise in government R&D spending. A public-private Energy Technology Institute was set up, and the research councils co-operated on a joint energy research program. By 2010 this had led to a significant rise in R&D, but a new government and its austerity policy reversed this, with a 23% cut in the cash budget in 2011.

The direction of the UK government’s current energy policy is, to be polite, not wholly clear. Painfully slow moves are being made to secure some nuclear new build, the government is hanging back from supporting proposals to implement carbon capture and sequestration at scale, current renewables are facing difficulties of politics and cost, and the issue of climate change has been sidelined. Current scenarios anticipate a substantial increase in electricity generation from gas without carbon capture. You could make a case that current renewables are too expensive, and we should use a combination of gas and nuclear as a stop-gap while we wait for new technologies to emerge. But they won’t emerge unless someone does the research and development work to make them happen. The inaction of the last couple of decades mean that we’ve got a huge amount of ground to make up. I don’t yet see the will to develop the capacity we need to do this, and I don’t think the industry structure we’ve got helps.

Statistics on government energy RD&D expenditure from the International Energy Authority, on UK industry R&D from Office of National Statistics Business Enterprise R&D figures.

This sound very scary… Are the Scientific community politically organised? What are the political venues in the UK to do something about this (outside joining political parties).

Thanks for the insightfully essay

Zelah

Thermoplastics are recyclable, for a while at least. There are all polymer small batteries. There are polymer parts for large batteries (auto that might scale to utility). I hope conductive thermoplastics can be engineered that are mostly recyclable. I hope they can be used for utility-scale batteries. If not, at least wind and solar components. An initial goal would be to get petro-refinery energy sources from their own recyclable products instead of making anarchy. The more cheap oil we savee, the better pandemic infrastructures we will have. Lots of other materials to consider. Hopefully the plastic isn’t toxic, at least not to the general public.