I have a post up on the blog of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute – The failures of supply side innovation policy – discussing the connection between recent innovation policy in the UK and our current crisis of economic growth. Rather than cross-posting it here, I tell the same story in four graphs.

1. The UK’s current growth crisis follows a sustained period of national disinvestment in R&D

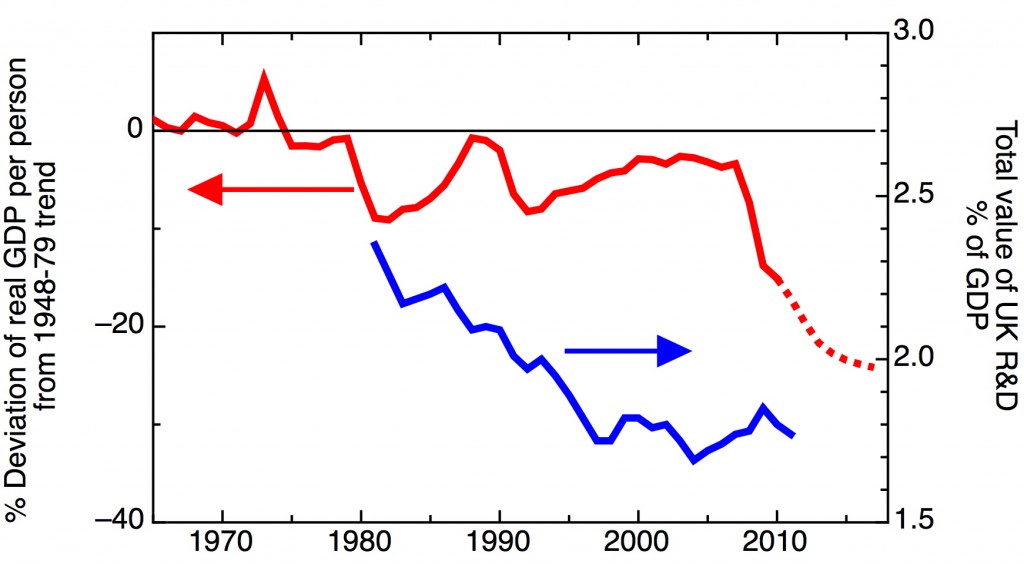

Red, left axis. The percentage deviation of real GDP per person from the 1948-1979 trend line, corresponding to 2.57% annual growth. Sources: solid line, 2012 National Accounts. Dotted line, March 2013 estimates from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility.

Blue, right axis. Total R&D intensity, all sectors, as percentage of GDP. Data: Eurostat.

No single measure can capture the overall performance of an economy, but the long term trajectory of real GDP per person in the UK tells an interesting story, with a clear discontinuity in 1979. From 1948 to 1979 this measure grew remarkably steadily; a best fit corresponds to 2.57% annual growth. Since 1979 we have seen two deep recessions, each followed by a period of faster growth that, in each case, didn’t quite make up the lost ground to the pre-1979 trend line, and proved unsustainable. The third recession, following the 2008 financial crisis, has been both deeper and more long lasting than previous recessions. Meanwhile, since 1980, there has been a substantial fall in the overall research intensity of the economy, measured by the fraction of GDP spent on research and development. Without claiming simple causality, my SPERI post looks at the relationship between our current growth crisis and this disinvestment in R&D.

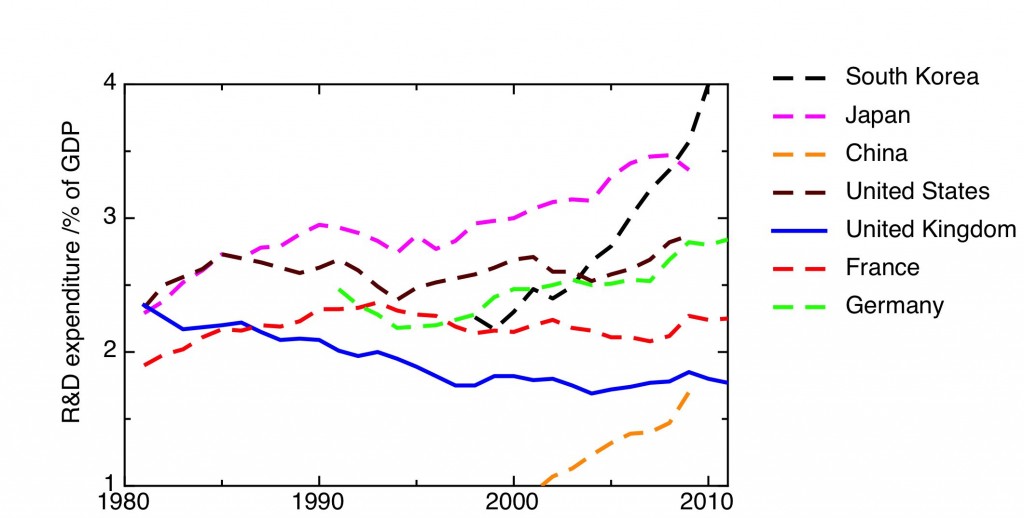

2. Since 1980, the UK has moved from being one of the most R&D intensive economies in the developed world, to one of the least.

Total R&D expenditure as % of GDP. Data: Eurostat

This decline in R&D intensity in the UK has happened at a time when other countries have been increasing investment in research. These increases have been particularly marked in fast growing Asian countries like South Korea and China.

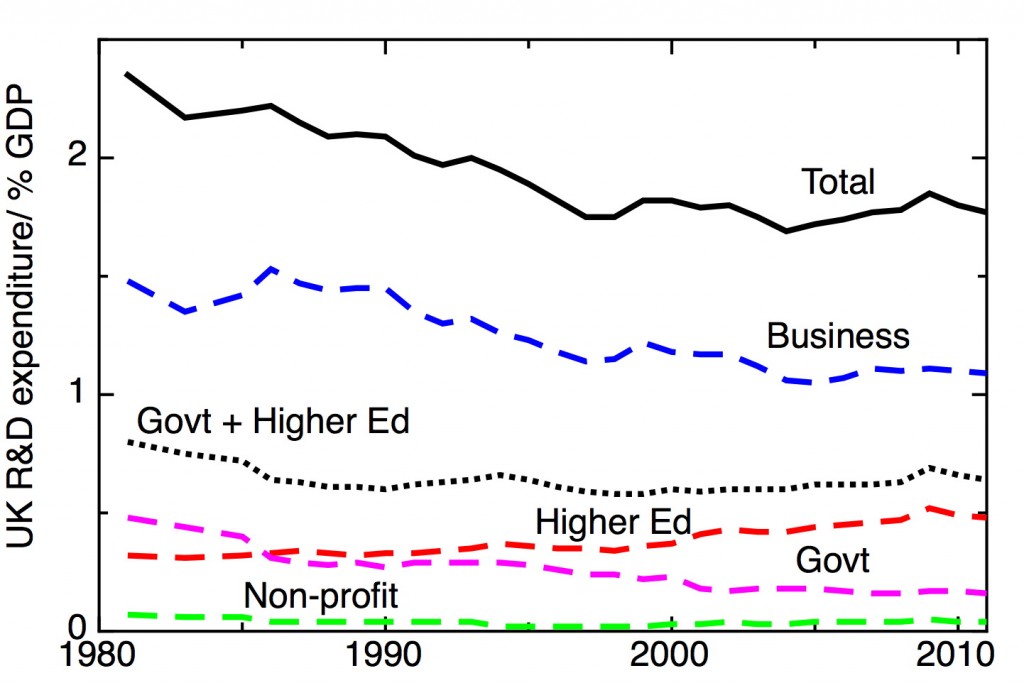

3. The overall decline in the UK’s R&D intensity has been driven primarily by a long- term decline in private sector R&D

Value of R&D performed by sector as % of GDP. Data: Eurostat

Most R&D is performed in the private sector, with other substantial contributions happening in Government laboratories and Universities. R&D in the combined Government and HE sectors in the UK dropped substantially in the 1980’s and then stabilised, but the largest decline has taken place in private sector R&D. One might be tempted to argue that this reflects changes in the sectoral balance of the UK economy, but a more detailed analysis by Alan Hughes and Andrea Mina shows that, even after adjusting for structural differences between countries, the business enterprise component of R&D remains low by international standards.

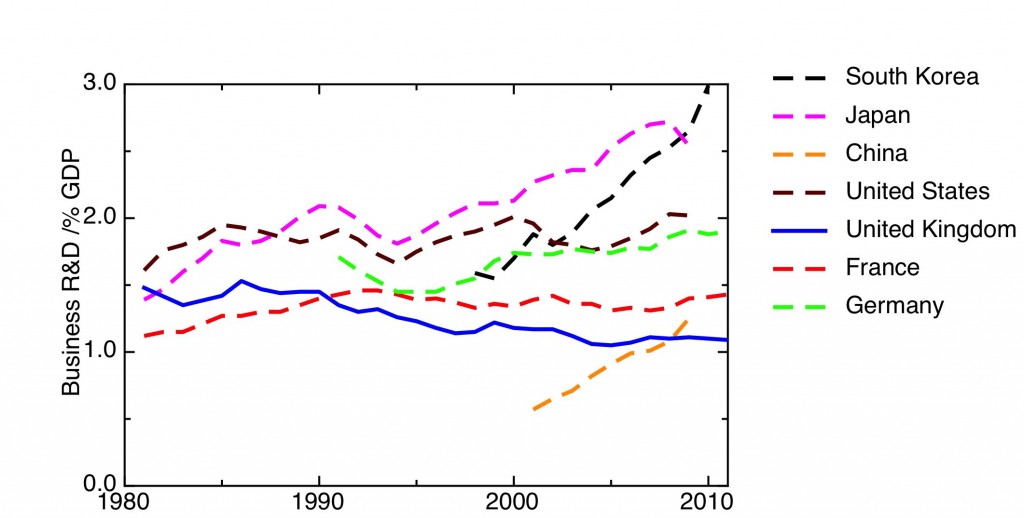

4. The relative value of R&D performed in the business sector in the UK has been falling since the mid-1980s and has slipped far behind key rivals

Value of R&D performed by the business sector as % of GDP. Source: Eurostat

The contrast between the declining R&D intensity of the UK’s private sector and its growth in competitor nations is marked. My SPERI blogpost The failures of supply side innovation policy explores what might lie behind this.

Really enjoyed reading the blogs, packed with evidence & very readable. I guess the question that springs to mind is

given the political economy and other priorities of health, international development etc how do we make the case for the “dramatic intervention” (in your other blog)?

And graph 4 shows the gaps are big. So where and how do we target resource?

I would think the aging populations of Europe and the rest of the developed economies would provide the increased demand for effective anti-aging bio-medicine. Yet, the institutions that do this kind of research seem not to be responding to such demand incentives at all. This suggests institutional issues.

Professor Jones: “The areas in which society needs innovation now are clear…”

I’m not so sure it is. Nature is unimpressed with a private banking system that has deliberately decided that financial asset manipulation should consume the lions share of resources.

A con game remains a con game even if you switch to government intervention controlled by oligarchs. The futility in this scheme becomes obvious for whatever productivity improvement is rendered irrelevant in a state of perpetual insolvency. The eventual and desired outcome is always privatization of public infrastructure.

The constant drum beat of Innovation by the financial elites is a neat distraction from the steady march towards poverty

Thanks Sarah. I think the priorities have to be determined by a combination of where we have strengths to build on already, and where the needs are most pressing (energy and healthcare in particular).

Abelard, I think the problem is partly institutions, partly the intrinsic difficulty of the problems. To take the specific example of therapies for Alzheimer’s we can see that there are, in fact, three linked problems. We know far too little about the basic causes of the problem, too few scientists work on it, and because of this when pharma companies do try to bring therapies to market they don’t work. The more failed drugs there are, the less the incentives will be for people to put in the very large sums of money needed to find new ones, no matter how big the demand incentives are.

I wish I could easily refute Randall’s pessimism.

I think these philosophies can also be traced, to some degree, to society. We live in an age where people want results faster. Many Asian countries tend to seek guidance from doing things “wisely” and through perseverance. I can’t say this with any certainty, but it’s possible that in the long term, those countries that invest in R&D will reap the rewards in the long haul…certainly something your graphs show, historically, to be true.

Part/most of why there is a valley of death is mass production/markets. Nanotechnology is prototyped so quickly that scale-up to mass market is retarded by future innovations or the prospect of future innovations. It is possible to pick winners if you can define what the future needs/wants to be prosperous. On the anarchy (market forces) end of things I’m a little worried data-mining software coupled with some automated faculties will lead to a war with the machines. On the tyranny risk end of things it would be nice to codify curriculums (ie. some Humanities) and life experiences and brain states that make people good and creative. Other than those two caveats it would be nice to promote a lot of R+D.

The Western world has been deindustrializing for quite a while (at least since the ’80s) and moving towards (and has become) a set of mostly service industry economies. As a result, innovations that aren’t useful for service industries could be ignored/shunned because people can’t compete by using national industry. Those that try usually fail when competing against competitors who outsource to China. In other words: I think we’re looking at the consequences of globalization here.