The iPhone must be one of the most instantly recognisable symbols of the modern “tech economy”. So, it was an astute choice by Mariana Mazzacuto to put it at the centre of her argument about the importance of governments in driving the development of technology. Mazzacuto’s book – The Entrepreneurial State – argues that technologies like the iPhone depended on the ability and willingness of governments to take on technological risks that the private sector is not prepared to assume. She notes also that it is that same private sector which captures the rewards of the government’s risk taking. The argument is a powerful corrective to the libertarian tendencies and the glorification of the free market that is particularly associated with Silicon Valley.

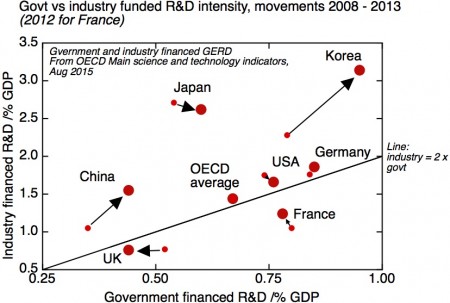

Her argument could, though, be caricatured as saying that the government built the iPhone. But to put it this way would be taking the argument much too far – the contributions, not just of Apple, but of many other companies in a worldwide supply chain that have developed the technologies that the iPhone integrates, are enormous. The iPhone was made possible by the power of private sector R&D, the majority of it not in fact done by Apple, but by many companies around the world, companies that most people have probably not even heard of.

And yet, this private sector R&D was indeed encouraged, driven, and indeed sometimes funded outright, by government (in fact, more than one government – although the USA has had a major role, other governments have played their parts too in creating Apple’s global supply chain). It drew on many results from publicly funded research, in Universities and public research institutes around the world.

So, while it isn’t true to say the government built the iPhone, what is true is to say that the iPhone would not have happened without governments. We need to understand better the ways government and the private sector interact to drive innovation forward, not just to get a truer picture of where the iPhone came from, but in order to make sure we continue to get the technological innovations we want and need.

Integrating technologies is important, but innovation in manufacturing matters too

The iPhone (and the modern smartphone more generally) is, truly, an awe-inspiring integration of many different technologies. It’s a powerful computer, with an elegant and easy to use interface, it’s a mobile phone which connects to the sophisticated, computer driven infrastructure that constitutes the worldwide cellular telephone system, and through that wireless data infrastructure it provides an interface to powerful computers and databases worldwide. Many of the new applications of smartphones (as enablers, for example, of the so-called “sharing economy”) depend on the package of powerful sensors they carry – to infer its location (the GPS unit), to determine what is happening to it physically (the accelerometers), and to record images of its surroundings (the camera sensor).

Mazzacuto’s book traces back the origins of some of the technologies behind the iPod, like the hard drive and the touch screen, to government funded work. This is all helpful and salutary to remember, though I think there are two points that are underplayed in this argument.

Firstly, I do think that the role of Apple itself (and its competitors), in integrating many technologies into a coherent design supported by usable software, shouldn’t be underestimated – though it’s clear that Apple in particular has been enormously successful in finding the position that extracts maximum value from physical technologies that have been developed by others.

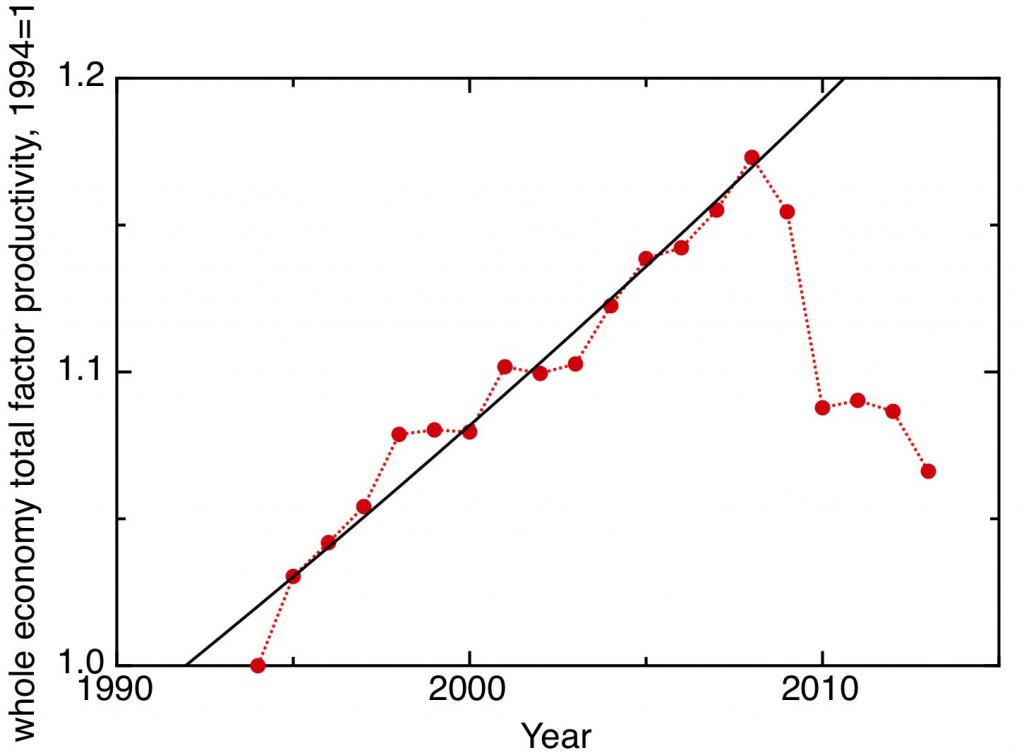

Secondly, when it comes to those physical technologies, one mustn’t underestimate the effort that needs to go in to turn an initial discovery into a manufacturable product. A physical technology – like a device to store or display information – is not truly a technology until it can be manufactured. To take an initial concept from an academic discovery or a foundational patent to the point at which one has a a working, scalable manufacturing process involves a huge amount of further innovation. This process is expensive and risky, and the private sector has often proved unwilling to bear these costs and risks without support from the state, in one form or another. The history of some of the many technologies that are integrated in devices like the iPhone illustrate the complexities of developing technologies to the point of mass manufacture, and show how the roles of governments and the private sector have been closely intertwined.

For example, the ultraminiaturised hard disk drive that made the original iPod possible (now largely superseded by cheaper, bigger, flash memory chips) did indeed, as pointed out by Mazzucato, depend on the Nobel prize-winning discovery by Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg of the phenomenon of giant magnetoresistance. This is a fascinating and elegant piece of physics, which suggested a new way of detecting magnetic fields with great sensitivity. But to take this piece of physics and devise a way of using it in practise to create smaller, higher capacity hard disk drives, as Stuart Parkin’s group at IBM’s Almaden Laboratory did, was arguably just as significant a contribution.

How liquid crystal displays were developed

The story of the liquid crystal display is even more complicated. Continue reading “Did the government build the iPhone? Would the iPhone have happened without governments?”