An important milestone in the use of nanoparticles to deliver therapeutic molecules is reported in this week’s Nature – full paper (subscription required), editors summary. See also this press release. The team, led by Mark Davis from Caltech, used polymer nanoparticles to deliver small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules into tumour cells in humans, with the aim of preventing the growth of these tumours.

I wrote in more detail about siRNA back in 2005 here. If one can introduce the appropriate siRNA molecules into a cell, they can selectively turn off the expression of any gene in that cell’s genome, potentially giving us a new class of powerful drugs which would be an absolutely specific treatment both for viral diseases and cancers. When I last wrote about this subject, it was clear that the problem of delivering of these small strands of RNA to their target cells was going to be a major barrier to fulfilling the promise of this very exciting new technology. In this paper, we see that substantial progress has been made towards overcoming this barrier. In this study the RNA was incorporated in self-assembled polymer nanoparticles, the surfaces of which were decorated with groups that selectively bind to proteins that are found on the surfaces of the tumour cells being targeted.

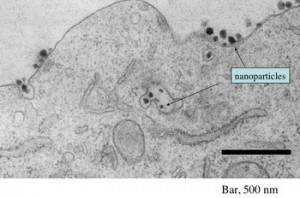

The experiments were carried out as part of a phase 1 clinical trial on humans. What the Nature paper shows is that the nanoparticles do indeed accumulate at tumour cells and are incorporated within them (see the micrograph below), and that the siRNA does suppress the synthesis of the particular protein at which it is aimed, a protein which is necessary for the growth of the tumour. If this trial doesn’t demonstrate unacceptable harmful effects, further clinical trials will be needed to demonstrate whether the therapy works clinically to arrest the growth of these tumours.