This somewhat policy-heavy piece is an updated version of a talk I gave at a higher education policy conference last September – my apologies for blog readers not directly concerned with science and University funding in the UK, who may find it less enthralling.

What is this thing called “impact”, which has such a grip on Universities and funding agencies in the UK at the moment? Of course, it isn’t a thing at all; it’s a word that’s been adopted to stand for a number of overlapping, but still distinct, imperatives that are being felt by different public agencies concerned with different aspects of funding research in higher education in the UK, and which, in turn, different constituencies within UK higher education are attempting to steer.

The most immediate sources of talk about “impact” are the Higher Education Funding Council of England (HEFCE) and the different research councils, who operate jointly in this area under the umbrella of Research Councils UK (RCUK). These two manifestations of this impact agenda are, in fact, two rather different and separate issues. HEFCE wish to measure the impact of past research, as part of their overall program to assess the past research performance of Universities – the Research Excellence Framework – which subsequently will inform future allocations of funding to the Universities. RCUK, on the other hand, wishes to ensure that the research it funds is carried out in a way that maximises the chance that it does have impact. Both HEFCE and RCUK want the idea of impact to have a greater influence on funding decisions. But HEFCE’s version of impact is backward looking and concerned with measurement, RCUK’s interest is forward looking and concerned with changing behaviours.

It is important to understand the wider context which has driven this concern with impact. The immediate pressure has come from the funding council’s perception of a growing need to convince the Treasury that public spending on research brings a proportionate return to the UK as a whole. During the process of settling the science budget last autumn, in a very tight public spending round, this argument within government, has been dominant. And, to the extent that the budget settlement was not as bad as many had feared, perhaps this idea of impact did gain some traction. Certainly, last December’s letter (PDF here) announcing the science settlement called for “even more impact” – saying “Research Councils and Funding Councils will be able to focus their contribution on promoting impact through excellent research, supporting the growth agenda. They will provide strong incentives and rewards for universities to improve further their relationships with business and deliver even more impact in relation to the economy and society.”

But this focus on impact is only one manifestation of a much wider discussion about the value of research to society at large and how the values that underly publicly funded research should be aligned with widely shared societal values. The broader question is how we organise publicly funded research to realise its public value. For leaders and managers of HE institutions engaged in publicly funded research, this leads to fundamental questions about the missions and visions of their institutions and how this is communicated to their members.

What do we actually mean by “impact”? This, of course, is a highly contested question – there is a growing perception that the degree to which a particular discipline has a greater or lesser degree of impact on the wider world is directly connected to its value in the eyes of funding agencies, and so it’s not surprising that disciplines will wish to influence the definition of impact to maximise their contributions. Clearly science, engineering, medicine, social sciences, arts and the humanities will come at the problem with different emphases. The funding agencies will reflect a compromise position back to the academic communities they serve, while tailoring the message a different way in their interactions with their political masters.

HEFCE must, necessarily, take a broad view of impacts, as they serve the whole academic community. Engineers may emphasise the direct economic benefits that come from their research, social scientists information to underpin good public policy, while the humanities possibly more intangible cultural benefits. The task that HEFCE has set itself is devising a framework to measure and compare these incommensurable qualities. The methodology is starting to become clear. A pilot exercise tested a trial methodology in a number of different Universities in a handful of rather different subjects. The methodology combines the use of quantitative indicators, where appropriate, and narrative case studies, in which the external impact of research carried out by groups of researchers over some past period is described. The results of the pilot highlighted some predictable difficulties, and suggested some mitigating strategies. The timescales on which impact appears vary greatly from subject to subject, and even within subjects. For much research, impacts are captured outside higher education, whether that’s as a result of transfer of people from HE into industry or public service, or by the picking up of research ideas that are effectively in the public domain. As a result, the originators of research may well not be in a position to know about the impacts of their research.

The research councils have the apparent advantage that they can tailor the idea of impact more closely to their own constituencies. For the Medical Research Council (MRC), for example, it’s clear that improved health and well-being will be the primary category of their impact (though even here there may be many different routes to achieving those broad goals). The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) will tend to emphasise economic impacts through spin-outs and partnerships with existing industry. Many researchers will be concerned that the growing emphasis on impact will lead inexorably towards a move from pure, curiosity-driven research to more applied research. The counter-argument from the research councils will be to emphasise that this is not what they want; instead they seek a more conscious consideration of why the impact of the research they sponsor matters. This emphasises the forward-looking nature of the impact agenda as understood by RCUK – the sections in research council grant applications about “pathways to impact” don’t seek to ask researchers to predict the future, instead they seek to change the behavior of researchers.

It’s clear that defining and assessing impact isn’t easy; the Science Minister, David Willetts, had earlier made his reservations about this clear. In a speech in July last year he announced a delay in the Research Excellence Framework, saying “The surprising paths which serendipity takes us down is a major reason why we need to think harder about impact. There is no perfect way to assess impact, even looking backwards at what has happened. I appreciate why scientists are wary, which is why I’m announcing today a one-year delay to the implementation of the Research Excellence Framework, to figure out whether there is a method of assessing impact which is sound and which is acceptable to the academic community. This longer timescale will enable HEFCE, its devolved counterparts, and ministers to make full use of the pilot impact assessment exercise which concludes in the Autumn, and then to consider whether it can be refined. “

At the moment, though, the views of the Treasury are as important as the views of the Minister. It’s difficult to avoid the suspicion that, for all the subtlety with which RCUK and HEFCE have defined the many dimensions of impact, the Treasury is interested in only one type of impact – money. This sounds more straightforward, but it’s still not easy – we need for a robust evidence base for the assertion that spending on research yields tangible commensurate economic returns.

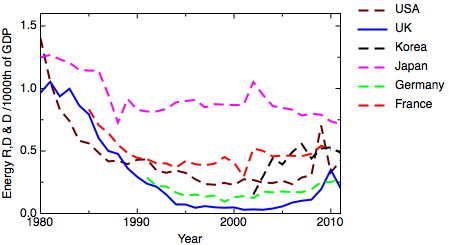

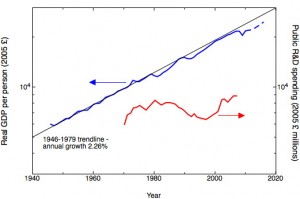

It isn’t just in the UK that these arguments are being carried on. In the USA, for example, the large injection of funding into science as part of the economic stimulus package have prompted the “Star Metrics” programme. In the UK, the Royal Society released in March last year an extensive study – “The Scientific Century” – which marshalled the evidence for the returns on investment in publicly funded R&D (concentrating on science, medicine and engineering).

Even in this restricted domain, the complications of the routes by which public investment in research produce returns become apparent. There was, for many years, a clear consensus in western countries about the way in which the value of publicly funded science emerges. This consensus originates in an enormously influential document written by the US science administrator, Vannevar Bush, in 1945 – “Science: the Endless Frontier”. This is the document that led to the foundation of the USA’s National Science Foundation. It encapsulated what, to many people, has become known as the “linear model of innovation” – the idea that pure science, curiosity driven and carried out without any consideration of its end-uses, would be converted into national prosperity through a linear process of applied science and technological development. Of course, the impact agenda, as conceived by the research councils, is in direct contradiction of this world-view – and since this view is deeply ingrained in many parts of the scientific community, this accounts for the deep-seated unease in those quarters that the RCUK view of impact gives rise to. And, if it were that simple, surely the measurement of past impacts would be straightforward?

However, the linear model is now very much out of fashion – it is considered by many to be neither an accurate picture of how research has worked in the past, nor a desirable prescription for how research ought to work in the future. To return to our current Science Minister, it is clear that he doesn’t believe it at all. In his July speech, he said: “The previous government appeared to think of innovation as if it were a sausage machine. You’re supposed to put money into university-based scientific research, which leads to patents and then spinout companies that secure venture capital backing….The world does not work like this as often as you might think…. There are many other ways of harvesting benefits from research. But the benefits are real”.

One of the most influential critiques of the linear model came in a came in a book by Donald Stokes called Pasteur’s quadrant. This argued that the separation of basic research from considerations of potential applications which is made explicit in Bush’s picture didn’t always correspond to the reality of how research has been done. There have certainly been scientists who have carried out fundamental investigations without any thought of potential use – Niels Bohr is the example Stokes used. And, as Bush argued, sometimes very practical applications do in fact emerge from such work. There have been technologists who have focused solely on the need to get their inventions to work and to market, without a great deal of curiosity about the fundamental underpinnings of those technologies – Thomas Edison being a classical example. But a scientist like Louis Pasteur carried out fundamental research – in his case, laying many of the foundations of modern microbiology, while at the same time being motivated by the very practical considerations of how wine ferments and milk sours.

On Stokes’s diagram, which has two axes defined by the degree to which considerations of use and fundamental interest motivate research, we have three quadrants typified by the approach of Bohr, Edison and Pasteur. What occupies the fourth quadrant, where the work is characterised by being neither fundamentally interesting nor practically useful? In the past this undesirable quadrant hasn’t had a name, but I propose to call it “Cable’s quadrant”, after the UKs secretary of state for Business, Innovation and Skills, who said in a speech on 8 September last year “there is no justification for taxpayers money being used to support research which is neither commercially useful nor theoretically outstanding.” Of course, no-one sets out to carry out research of this kind; the question is how to minimise the chance of research turning out this way without the risk of discouraging high-risk research that, if it did succeed, would be truly transformative.

There remains an unanswered question in Stokes’s formulation – who decides what is practically useful? Is this simply a matter of what has commercial applications? In the context of UK publicly funded research, this must be related to the broader question of who we, in Universities, work for. Universities are independent and autonomous institutions, so while they must respond to the immediate demands of their funders, they must always be mindful of their enduring sense of mission. How can we resolve this tension? One idea that might be helpful is the notion of “public value”, as applied to science policy in a pamphlet from Demos – The public value of science”. But it should be clear that the drive for research councils, in particular, to move beyond criteria for “good science” that are entirely defined by scientists, on the basis of their own disciplinary norms, to judging science on the basis of what are perceived as the needs of the nation, will present some severe problems of its own, which I will perhaps discuss in a later post.