Last night I gave a lecture at UCL to launch their new centre for Responsible Research and Innovation. My title was “Can innovation ever be responsible? Is it ever irresponsible not to innovate?”, and in it I attempted to put the current vogue within science policy for the idea of Responsible Research and Innovation within a broader context. If I get a moment I’ll write up the lecture as a (long) blogpost but in the meantime, here is a PDF of my slides.

Author: Richard Jones

Your mind will not be uploaded

The recent movie “Transcendence” will not be troubling the sci-fi canon of classics, if the reviews are anything to go by. But its central plot device – “uploading” a human consciousness to a computer – remains both a central aspiration of transhumanists, and a source of queasy fascination to the rest of us. The idea is that someone’s mind is simply a computer programme, that in the future could be run on a much more powerful computer than a brain, just as one might run an old arcade game on a modern PC in emulation mode. “Mind uploading” has a clear appeal for people who wish to escape the constraints of our flesh and blood existence, notably the constraint of our inevitable mortality.

In this post I want to consider two questions about mind uploading, from my perspective as a scientist. I’m going to use as an operational definition of “uploading a mind” the requirement that we can carry out a computer simulation of the activity of the brain in question that is indistinguishable in its outputs from the brain itself. For this, we would need to be able to determine the state of an individual’s brain to sufficient accuracy that it would be possible to run a simulation that accurately predicted the future behaviour of that individual and would convince an external observer that it faithfully captured the individual’s identity. I’m entirely aware that this operational definition already glosses over some deep conceptual questions, but it’s a good concrete starting point. My first question is whether it will be possible to upload the mind of anyone reading this now. My answer to this is no, with a high degree of probability, given what we know now about how the brain works, what we can do now technologically, and what technological advances are likely in our lifetimes. My second question is whether it will ever be possible to upload a mind, or whether there is some point of principle that will always make this impossible. I’m obviously much less certain about this, but I remain sceptical.

This will be a long post, going into some technical detail. To summarise my argument, I start by asking whether or when it will be possible to map out the “wiring diagram” of an individual’s brain – the map of all the connections between its 100 billion or so neurons. We’ll probably be able to achieve this mapping in the coming decades, but only for a dead and sectioned brain; the challenges for mapping out a living brain at sub-micron scales look very hard. Then we’ll ask some fundamental questions about what it means to simulate a brain. Simulating brains at the levels of neurons and synapses requires the input of phenomenological equations, whose parameters vary across the components of the brain and change with time, and are inaccessible to in-vivo experiment. Unlike artificial computers, there is no clean digital abstraction layer in the brain; given the biological history of nervous systems as evolved, rather than designed, systems, there’s no reason to expect one. The fundamental unit of biological information processing is the molecule, rather than any higher level structure like a neuron or a synapse; molecular level information processing evolved very early in the history of life. Living organisms sense their environment, they react to what they are sensing by changing the way they behave, and if they are able to, by changing the environment too. This kind of information processing, unsurprisingly, remains central to all organisms, humans included, and this means that a true simulation of the brain would need to be carried out at the molecular scale, rather than the cellular scale. The scale of the necessary simulation is out of reach of any currently foreseeable advance in computing power. Finally I will conclude with some much more speculative thoughts about the central role of randomness in biological information processing. I’ll ask where this randomness comes from, finding an ultimate origin in quantum mechanical fluctuations, and speculate about what in-principle implications that might have on the simulation of consciousness.

Why would people think mind uploading will be possible in our lifetimes, given the scientific implausibility of this suggestion? I ascribe this to a combination of over-literal interpretation of some prevalent metaphors about the brain, over-optimistic projections of the speed of technological advance, a lack of clear thinking about the difference between evolved and designed systems, and above all wishful thinking arising from people’s obvious aversion to death and oblivion.

On science and metaphors

I need to make a couple of preliminary comments to begin with. First, while I’m sure there’s a great deal more biology to learn about how the brain works, I don’t see yet that there’s any cause to suppose we need fundamentally new physics to understand it. Continue reading “Your mind will not be uploaded”

Transhumanism has never been modern

Transhumanists are surely futurists, if they are nothing else. Excited by the latest developments in nanotechnology, robotics and computer science, they fearlessly look ahead, projecting consequences from technology that are more transformative, more far-reaching, than the pedestrian imaginations of the mainstream. And yet, their ideas, their motivations, do not come from nowhere. They have deep roots, perhaps surprising roots, and following those intellectual trails can give us some important insights into the nature of transhumanism now. From antecedents in the views of the early 20th century British scientific left-wing, and in the early Russian ideologues of space exploration, we’re led back, not to rationalism, but to a particular strand of religious apocalyptic thinking that’s been a persistent feature of Western thought since the middle ages.

Transhumanism is an ideology, a movement, or a belief system, which predicts and looks forward to a future in which an increasing integration of technology with human beings leads to a qualititative, and positive, change in human nature. Continue reading “Transhumanism has never been modern”

Rebuilding the UK’s innovation economy

The UK’s innovation system is currently under-performing; the amount of resource devoted to private sector R&D has been too low compared to competitors for many years, and the situation shows no sign of improving. My last post discussed the changes in the UK economy that have led us to this situation, which contributes to the deep-seated problems of the UK economy of very poor productivity performance and persistent current account deficits. What can we do to improve things? Here I suggest three steps.

1. Stop making things worse.

Firstly, we should recognise the damage that has been done to the countries innovative capacity by the structural shortcomings of our economy and stop making things worse. R&D capacity – including private sector R&D – is a national asset, and we should try and correct the perverse incentives that lead to its destruction. Continue reading “Rebuilding the UK’s innovation economy”

Business R&D is the weak link in the UK’s innovation system

What’s wrong with the UK’s innovation system is not that we don’t have a strong science base, or even that there isn’t the will to connect the science base to the companies and entrepreneurs who might want to use its outputs. The problem is that our economy isn’t assigning enough resource to pulling through the fruits of the science base into technological innovations, the innovation that will create new products and services, bring economic growth, and help solve some of the biggest social problems we face. The primary symptom of the problem is the UK’s very poor performance at business funded research and development R&D. This is the weak link in the UK’s national innovation system, and it is part of a bigger picture of short-termism and under-investment which underlie the UK economy’s serious long-term problems.

For context, it’s worth highlighting two particular features of the UK economy. The first is its very poor productivity growth: currently on one measure (annualised 6 year growth in productivity) we’re seeing the worst peace-time performance for the last 150 years. Without productivity growth, there will be no growth in average living standards, and that’s going to lead to an increasingly sour political scene.

The second is the huge current account deficit, which at 5.4% of GDP is worse than in the crisis years of the mid-1970s. Now, as then, the UK is unable to pay its way in the world. Unlike the 1970’s, though, there’s no immediate political crisis, no humiliating appeals to the IMF for a bail-out. This time round, overseas investors are happy to finance this deficit by buying UK assets. But this isn’t cost-free. An influx of overseas capital is what is currently driving a price bubble for domestic and commercial property in London, severely unbalancing the economy and leading to a growing gulf between the capital and the regions. The assets being bought include the nation’s key infrastructure in energy and transport; there will be an inevitable loss of control and sovereignty as more of this infrastructure falls into overseas ownership. Chinese money will be paying for any new generation of nuclear power stations that will be built; that will give the UK very little leverage in insisting that some of that investment is spent to create jobs in the UK, and it will be paid for by what will effectively be a tax on everyone’s electricity bills, guaranteed for 35 years.

These are long-term problems, and so is the decline in business R&D intensity. The last thirty years has seen this drop from 1.48% in 1981, to 1.09% now (measured as a percentage of GDP) Continue reading “Business R&D is the weak link in the UK’s innovation system”

Surely there’s more to science than money?

How can we justify spending taxpayers’ money on science when there is so much pressure to cut public spending, and so many other popular things to spend the money on, like the National Health Service? People close to the policy-making process tend to stress that if you want to persuade HM Treasury of the need to fund science, there’s only one argument they will listen to – that science spending will lead to more economic growth. Yet the economic instrumentalism of this argument grates for many people. Surely it must be possible to justify the elevated pursuit of knowledge in less mercenary, less meretricious terms? If our political economy was different, perhaps it would be possible. But in a system in which money is increasingly seen as the measure of all things, it’s difficult to see how things could be otherwise. If you don’t like this situation, it’s not science, but broader society, that you’ve got to change.

The relentless focus on the economic justification of science is relatively recent, but that doesn’t mean that what went before was a golden age. The dominant motivation for state support of science in the twentieth century wasn’t to make money, but to win wars. Continue reading “Surely there’s more to science than money?”

Spin-outs and venture capital won’t fill the pharma R&D gap

Now that Pfizer has, for the moment, been rebuffed in its attempt to take over AstraZeneca, it’s worth reflecting on the broader issues this story raised about the pharmaceutical industry in particular and technological innovation more generally. The political attention focused on the question of industrial R&D capacity was very welcome; this was the subject of my last post – Why R&D matters. Less has been said about the broader problems of innovation in the pharmaceutical industry, which I discussed in an earlier post – Decelerating change in the pharmaceutical industry. One of the responses I had to my last post argued that we shouldn’t worry about declining R&D in the pharmaceutical industry, because that represented an old model of innovation that was being rapidly superseded. In the new world, nimble start-ups, funded by far-seeing venture capitalists, are able to translate the latest results from academic life sciences into new clinical treatments in a much more cost-effective way than the old industry behemoths. It’s an appealing prospect that fits in with much currently fashionable thinking about innovation, and one can certainly find a few stories about companies founded that way that have brought useful treatments to market. The trouble is, though, if we look at the big picture, there is no evidence at all that this new approach is working.

A recent article by Matthew Herper in Forbes – The Cost Of Creating A New Drug Now $5 Billion, Pushing Big Pharma To Change – sets out pharma’s problems very starkly. Continue reading “Spin-outs and venture capital won’t fill the pharma R&D gap”

Why R&D matters

The takeover bid for the UK/Swedish pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca by US giant Pfizer has given rare political prominence to the issue of UK-based research and development capacity. Underlying much opposition to the deal is the fear that the combined entity will seek to cut costs, and that R&D expenditure will be first in the firing line. This fear is entirely well-founded; since Pfizer took over Wyeth in 2009 it has reduced total R&D spend from $11bn to $6.7bn, and in the UK Pfizer’s cost-cutting reputation was sealed by the closure of its Sandwich R&D facility in 2011. Nor is the importance of AstraZeneca to UK R&D capacity overstated. In the latest EU R&D scoreboard, of the top world 100 companies by R&D expenditure, only 2 are British. One of these is AstraZeneca, and the other GSK. And, if the deal goes ahead and does result in a significant reduction in UK R&D capacity, it wouldn’t be an isolated event. It would be the culmination of a 30 year decline in UK business R&D intensity, which has taken the UK from being one of the most R&D intensive economies in the developed world, to one of the least.

My recent paper “The UK’s Innovation Deficit and How to repair it” analysed this decline in detail and related it to changes in the wider political economy. One response I’ve had to the paper was to regard this decline in R&D intensity as something to be welcomed. In this view, R&D is a legacy of an earlier era of heavy industry and monolithic corporations, now obsolete in a world of open innovation, where valuable intellectual property is more likely to be a brand identity than a new drug or a new electronic device.

I think this view is quite wrong. This doesn’t mean that I think that those kinds of innovation that arise without formal research and development are not important; innovations in the way we organise ourselves, to give one example, can create enormous value. Of course, R&D in its modern sense is just such a social innovation. Continue reading “Why R&D matters”

The economics of innovation stagnation

What would an advanced economy look like if technological innovation began to dry up? Economic growth would begin to slow, and we’d expect the shortage of opportunities for new, lucrative investments to lead to a period of persistently lower rates of return on capital. The prices of existing income-yielding assets would rise, and as wealth-holders hunted out increasingly rare higher yielding investment opportunities we’d expect to see a series of asset price bubbles. As truly transformative technologies became rarer, when new technologies did come along we might see them being associated with hype and inflated expectations. Perhaps we’d also begin to see growing inequality, as a less dynamic economy cemented the advantages of the already wealthy and gave fewer opportunities to talented outsiders. It’s a picture, perhaps, that begins to remind us of the characteristics of the developed economies now – difficulties summed up in the phrase “secular stagnation”. Could it be that, despite the widespread belief that technology continues to accelerate, that innovation stagnation, at least in part, underlies some of our current economic difficulties?

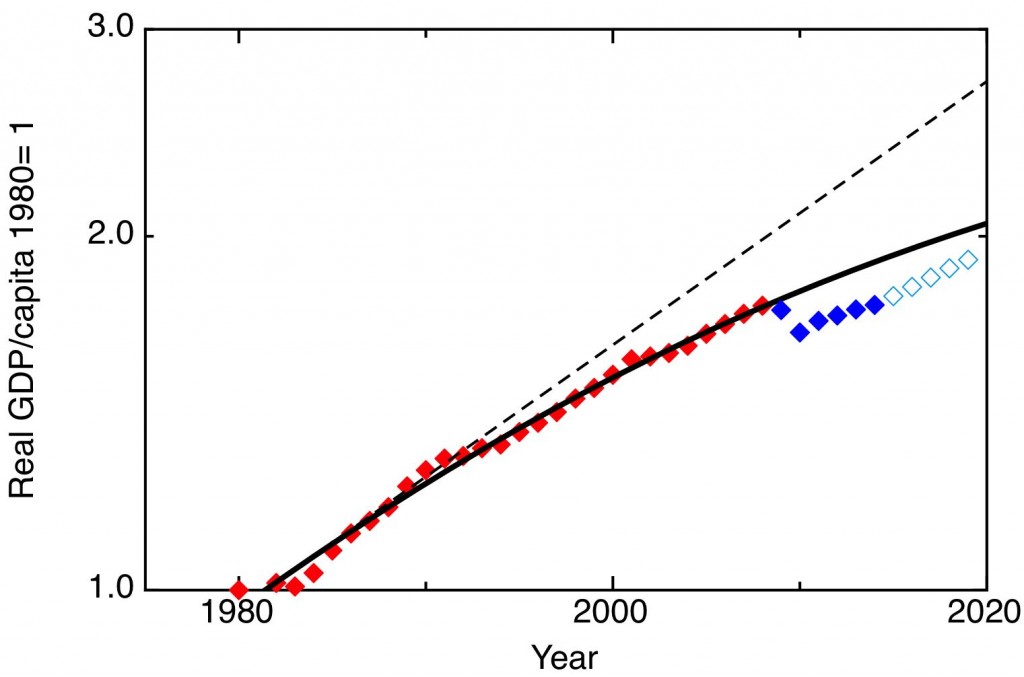

Growth in real GDP per person across the G7 nations. GDP data and predictions from the IMF World Economic Outlook 2014 database, population estimates from the UN World Population prospects 2012. The solid line is the best fit to the 1980 – 2008 data of a logistic function of the form A/(1+exp(-(T-T0)/B)); the dotted line represents constant annual growth of 2.6%.

The data is clear that growth in the richest economies of the world, the economies operating at the technological leading edge, was slowing down even before the recent financial crisis. Continue reading “The economics of innovation stagnation”

New Dawn Fades?

Before K. Eric Drexler devised and proselytised for his particular, visionary, version of nanotechnology, he was an enthusiast for space colonisation, closely associated with another, older, visionary for a that hypothetical technology – the Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill. A recent book by historian Patrick McCray – The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future – follows this story, setting its origins in the context of its times, and argues that O’Neill and Drexler are archetypes of a distinctive type of actor at the interface between science and public policy – the “Visioneers” of the title. McCray’s visioneers are scientifically credentialed and frame their arguments in technical terms, but they stand at some distance from the science and engineering mainstream, and attract widespread, enthusiastic – and sometimes adulatory – support from broader mass movements, which sometimes take their ideas in directions that the visioneers themselves may not always endorse or welcome.

It’s an attractive and sympathetic book, with many insights about the driving forces which led people to construct these optimistic visions of the future. Continue reading “New Dawn Fades?”