This the third and final in a series of three posts. The first part is here, and this follows on directly from part 2

(Added 2/9/2015: For those who dislike the 3-part blog format, the whole article can be downloaded as a PDF here: Innovation, research and development, and the UK’s productivity crisis).

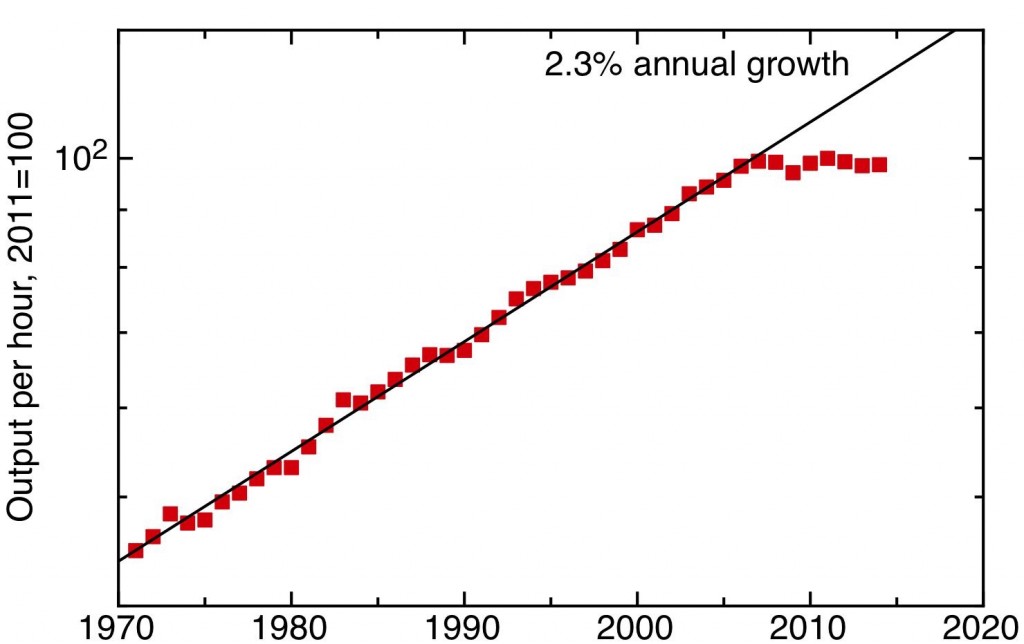

Quantifying the productivity benefits of research and development

The UK’s productivity problem is an innovation problem. This conclusion follows from the analysis of Goodridge, Haskel and Wallis, at least if one equates the economist’s construction of total factor productivity with innovation. This needs some qualification, because when economists talk about innovation in this context they mean anything that allows one to produce more economic output with the same inputs of labour and capital. So this can result from the development of new high value products or new, better processes to make existing products. Such developments are often, but not always, the result of formal research and development.

But there are many other types of innovation. People continually work out better ways of doing things, either as a result of formal training or simply by learning from experience, they act on suggestions from users, they copy better practises from competitors, they see new technologies in action in other sectors and apply them in their own, they work out more effective ways of organising and distributing their work; all these lead to total factor productivity growth and count as innovation in this sense.

There has been a tendency to underplay the importance of formal research and development in recent thinking about innovation, particularly in the UK. Continue reading “Innovation, research, and the UK’s productivity crisis – part 3”