This is a slightly expanded version of an article published last week in Research Professional – The latest industrial strategy has made choices

Last week’s Industrial Strategy Policy Paper is the latest chapter in the chequered history of UK Industrial Strategies. For nearly three decades after Thatcher’s ascent to power, the UK’s strategy was not to have an industrial strategy, which was a concept associated with money-losing supersonic airliners and cars with square steering wheels. But that conventional wisdom has been challenged by a global financial crisis and nearly two decades of economic stagnation, so after a number of stops and starts over the last decade, a fully developed Industrial Strategy has now arrived.

This strategy is not entirely new – there are strong echoes of the 2017 strategy from Theresa May’s government, driven by the then Business Secretary Greg Clark. The five “critical technologies” of the 2023 Science and Technology Framework are preserved, and other interventions of the previous government, like Investment Zones and Freeports, survive with only minor rebranding. This continuity is to be welcomed.

The first test of any strategy is whether it makes choices. Here I think the signals are positive. The Green Paper identified 8 key sectors, but now 30 detailed sub-sectors, “frontier industries”, are identified. This welcome degree of granularity has been underpinned by a detailed methodology, evaluating both the economic potential of the frontier industries, and the degree to which policy can have an impact.

So, under the banner of Advanced Manufacturing, aerospace and automobiles appear as expected, but perhaps the inclusion of agri-tech is less anticipated. Clean energy industries include wind (onshore, offshore and floating), fission and fusion, but not solar. There’s more focus on non-STEM-based sectors than in previous strategies, including creative, financial services and professional and business services. Unsurprisingly, given the current geopolitical situation, defence is prominent, but here the final list of frontier industries awaits the publication of a Defence Industrial Strategy.

The geographical aspect of industrial strategy is much more prominent in this strategy than in predecessors. An analysis of industrial clusters leans heavily on the previous government’s cluster map, as well as accepting the importance of increasing the productivity of the UK’s underperforming second tier cities. But in identifying those places with existing strengths in the strategy’s priority frontier industries, or with the potential for better exploiting agglomeration economies, some places won’t make the cut. There will be gaps in the Industrial Strategy map.

Discussions of industrial strategy distinguish between “horizontal” interventions, that aim to improve the business environment without discriminating between sectors, and “vertical” policies focusing on particular types of industry. Here, the signals are that even the more “horizontal” measures will be tilted in favour of the (roughly) 30 frontier industries.

Addressing the cost of energy is prominent here; the effect of the very cost of energy relative to overseas competitors on the viability of many UK industries has been much discussed recently. Perhaps just as important as the cost of energy are the delays in making new grid connections for industrial electricity. Here there will be difficult choices too; if industrial energy prices are lowered, someone else will have to pay more, whether that is the domestic consumer, or the tax-payer. We’re paying for policy choices made a decade (and longer) ago, which resulted in an over-reliance on gas & an underinvested network.

Other “horizontal” interventions include trade policy, access to finance, addressing regulation and removing planning barriers. Skills and innovation are two areas where the choice needs to be made about how much to direct policy towards one’s selected sectors.

The skills section seems slightly underpowered; it highlights skills shortages in the priority sectors, recognises that we have too many underqualified young people, and acknowledges that adult and continuing education has declined. But solving these problems is laid at the door of Skills England (and counterparts in devolved nations). An infographic makes a welcome assertion of the central role of universities in delivering an industrial strategy, but without recognising the pressure the sector is under.

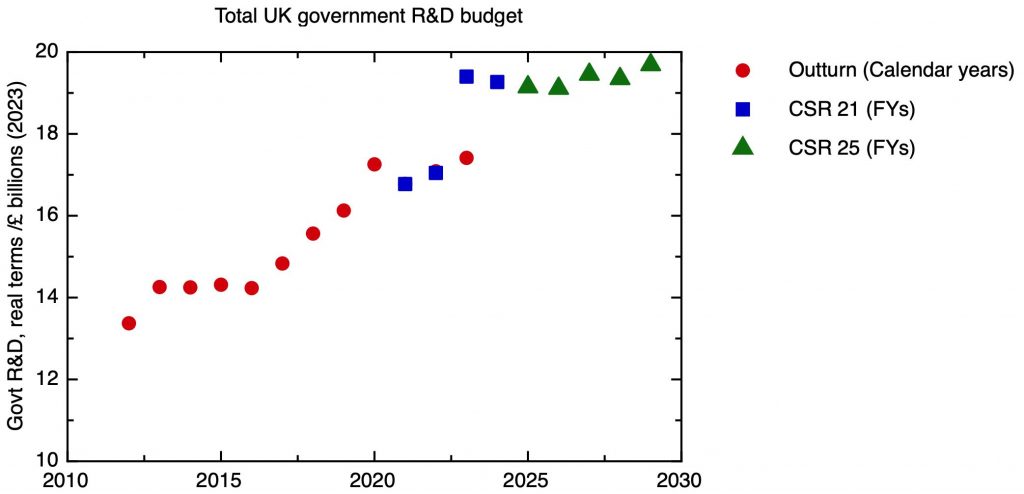

UK Government research and development spending since 2012. Outturn: ONS Research and development (R&D) expenditure by the UK government, 2023 Datasets. Allocations from CSR 2021 and CSR 2025 corrected for inflation using GDP deflators, OBR March 2025 predictions for future years.

For innovation, it’s appropriate to recognise that government spending on R&D is now at a high level – the last government did make significant increases in R&D spending, and the recent spending review locked those increases in place in real terms. The question will be, to what extent, that R&D spending will be directed at the industrial strategy priority areas.

Here the document is unequivocal on the principle – research funding, including that delivered through UKRI, will be pivoted towards the industrial strategy priorities. Again, the need to make choices is accepted. As widely trailed, R&D funding will be more rigorously sorted into three categories; basic curiosity-driven research, delivery of government priorities, and supporting private sector innovation-led growth. What remains to be decided are the relative size of these three buckets.

Will this industrial strategy deliver the economic growth that has been so lacking for nearly two decades? I think the two key requirements for success are genuine commitment across the whole of government, and consistency of purpose over time, with a mechanism for tracking progress and holding the government to account.

On the former, there are encouraging signs that the strategy has the support of Treasury; in addition to its sponsor department, the Department of Business and Trade, the priorities of DSIT and DESNZ are clearly reflected. But can the Home Office can be persuaded that some skilled immigration might be needed? Does DfE recognise that universities are actually quite an important part of the skills system?

Most importantly, this strategy probably needs a decade to make a significant impact. It’s good that it will be supported and monitored by an Industrial Strategy Council with statutory powers and supporting infrastructure. It would be even better if it could generate the kind of consensus that would allow it to survive the inevitable political changes to come.