It’s conventional to date the end of the Cold War to the break-up of the USSR, in 1991. Around that time, people started talking about a “Peace Dividend” – the economic benefits that would come as economies like the UK stood down from the partial war footing that they’d been operating under for the previous half-century. In the early 1980’s, the UK was spending more than 5% of its GDP on defence; in the late 80’s there was an easing of international tension, so by 1990 the fraction had already dropped to 4%. The end of the Cold War saw a literal cashing in of the peace dividend, with a fall in defence spending to around 2.5% in the 2000’s. The Coalition’s austerity policies bore down further on defence, with its share of GDP reaching a low point of 1.9% in 2017 [1].

But I’d argue that there was more to the post-cold-war peace dividend than the simple “guns or butter” argument, by which direct spending on the military could be redirected towards social programmes or to lower taxation. In the apparent absence of external threats, there is less pressure on governments to worry about the security of key inputs to the life of the nation. Rather than worrying about the security of food or energy supplies, there was a conviction that these things could be left to a globalising world market. Industries once thought of as “strategic” – such as semiconductors – could be left to fend for themselves, and if that led to their dismemberment and sale to foreign companies (as happened to GEC/ Marconi), then that could be rationalised as simply the benign outcome of the market efficiently allocating resources. Finally, in the apparent absence of external threats, for a government with an ideological prior for reducing the size of the state, a general run-down of state capacity seemed, if not an actual goal, to be an acceptable policy side-effect.

Things look different now. The invasion of Ukraine has brought Russia and NATO close to direct confrontation, and the resulting call for economic sanctions against Russia has shone a spotlight on the degree to which Europe has come to depend on Russia for supplies of oil and gas. This all takes place against the background of what’s starting to look like a chronic world polycrisis. As the effects of climate change become more obvious, we will see patterns of agriculture disrupted, stress on water supplies, people and communities driven from their homes. We’ll have to be more realistic about confronting the scale and speed of the necessary transition of our energy economy to net zero greenhouse gas emissions, and the economic and political disruptions that will lead to. And the pandemic that’s dominated our lives for the last couple of years isn’t likely to be the last.

The assumptions that became conventional wisdom in the benign years of the 1990s are now obsolete. I’m not convinced that politicians and opinion formers fully understand this yet. We not starting from a great place; the UK’s economy is already well into a second decade of very poor productivity growth, as I’ve been pointing out here for some time. This has led to a long period in which wages have stagnated; this is about to combine with a burst of inflation to produce an unprecedented drop in people’s real living standards. We are going to see increases in defence spending; there is more talk of resilience. But the talk of many senior politicians seems to speak more of a hope of a return to those benign years, more of a clinging on to old nostrums than a real willingness to rethink political and economic principles for these new times.

I don’t have any confidence that I know what those new political and economic principles should be. Here I’m just going to make some observations relevant to the narrower world of science and innovation policy. How might this new environment affect the priorities the state chooses for the science and innovation it supports?

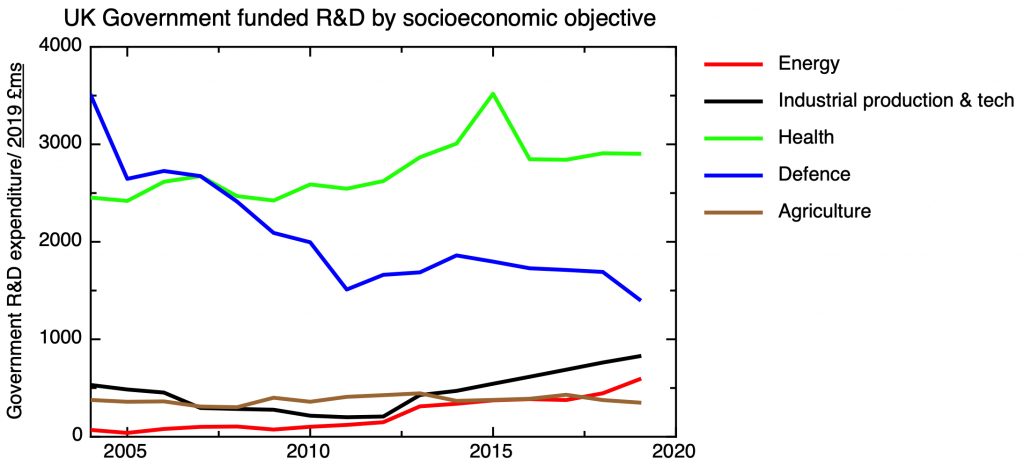

UK government research and development spending by socio-economic objective, for selected sectors. Data: Eurostat (GBARD)

My plot shows the way the division of UK government R&D between different socio-economic goals has evolved since 2004 [2]. The big story over the last twenty years has been the run down of defence R&D, and the increase in R&D related to health – another under-appreciated dimension of the peace dividend. In the heyday of the UK’s postwar “Warfare State” (as the historian David Edgerton has called it [3]), defence accounted for more than half of government R&D spending. As late as 2004, defence still accounted for 30% of the government’s expenditure, but by 2019 this fraction had fallen to 11%.

As for those other sectors that the warfare state would have regarded as of strategic importance – energy, agriculture and industrial production – by the mid-2000s, their shares of R&D had been run down to a few percent, or, in the case of energy, a fraction of a percent. Since then there has been some recovery – in the mid-2000’s, the government’s chief scientific advisor, Sir David King, very much aware of the issue of climate change, was instrumental in restoring some growth in energy R&D from the very low base it had reached. Meanwhile industrial strategy has made a slow and halting comeback, with increased government funding to agencies such as InnovateUK and collaborative initiatives in support of the aerospace and automotive sectors.

Now, the security of the nation, using that word in its broadest sense, no longer seems something we can take for granted. This will inevitably and rightly affect priorities for the government’s R&D spending. More emphasis on food and energy security, with a focus on driving down the cost of the transition to net zero; rebuilding sovereign capabilities in some areas of manufacturing; as well as a return to higher spending directly on defence R&D (including new threats to cybersecurity); these shifts seem inevitable and probably need to happen on a faster time-scale than many will be comfortable with. We won’t return to the world of the Warfare State, nor should we, but I don’t think the institutions we currently have are the right ones for a science and innovation policy driven by security and national resilience.

[1] Defense as fraction of GDP: SIPRI

[2] Gbard data from Eurostat.

[3] David Edgerton, Warfare State: Britain 1920 – 1970 (CUP). Historic defence R&D figures quoted on p259.