In the first part of this series attempting to sum up the issues facing UK science and innovation policy, I tried to set the context by laying out the wider challenges the UK government faces, asking what problems we need our science and innovation system to contribute to solving.

In the second part of the series, I posed some of the big questions about how the UK’s science and innovation system works, considering how R&D intensive the UK economy should be, the balance between basic and applied research, and the geographical distribution of R&D.

In the third part, I discussed the institutional landscape of R&D in the UK, looking at where R&D gets done in the UK.

In the fourth part, looking at the funding system, I considered who pays for R&D, and how decisions are made about what R&D to do.

In the fifth part, I looked in more detail at UK Research and Innovation, the government’s main agency for funding academic science.

There’s a tendency for analyses of the UK public R&D system to focus on the research councils that make up UKRI, because they are the most visible. But the UK government funds R&D in a number of other ways – for example through government departments – and it’s these other funding routes that I turn to in this section.

6.1. Other departmental science

Despite the systematic shift of UK government supported R&D from government applied research to “curiosity driven” research in HE between 1980 to 2010 that I described in part 2 of this series, a a substantial amount of government R&D is still routed through government departments, in support of those departments’ priorities.

Departmental science has always been vulnerable to budget cuts. The effects of cutting a research budget will only show up at some unspecified time in the future, so the temptation will always be for a department to sacrifice science in favour of immediate operating expenses. The 2010-2015 policy of austerity produced some dramatic falls in already small departmental research budgets. For the environment, the DEFRA R&D budget fell by 58% in real terms between 2010 and 2015, to £82 m/year, and since then has fallen further to £58m/yr. Transport R&D saw a 22% real terms cut, Education 53%, and the Home Office 60%, over the duration of the Coalition Government. It’s difficult to argue that all necessary innovation in these areas has already been done.

However, the biggest departmental spenders remain Defence, Health, and Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (outside the latter’s formal responsibility for the UKRI budget). These departments hold key responsibilities for the big challenges I outlined at the start of the series – productivity, energy/net zero, security and health, so it’s worth focusing on them in more detail.

6.2 The Ministry of Defence

The Ministry of Defence has a 20/21 R&D budget of £1.1 bn, and this is expected to rise substantially as the overall Defence budget itself increases. In Defence R&D, there’s a distinction between more long-ranged science and technology, and the expense of development and deployment of systems that are closer to application.

The 2020 Ministry of Defence science and technology strategy committed to spending 1.2% of the overall defence budget on science and technology, under the control of the MoD Chief Scientific Advisor. The total defence budget is projected to increase from £41.2 bn in 20/21 to £47.7bn in 24/25, so this implies a 15% increase in the science and technology budget, to £570m. One should also mention rising sums of money for R&D in the security services – with an allocation of £695m over 3 years.

As I wrote in an earlier blogpost Science and innovation policy in a new age of insecurity, it’s inevitable that in a more threatening world, we’ll see a return to higher direct spending directly on R&D for defense in its broadest sense. So the question now should be, are these increases enough, and are they directed in the right areas?

I don’t know the answer to this. A recent article in Nature highlighted some interesting comparisons. According to this,

the USA spent about $80 bn in 2020 on defence R&D, a factor of 60-fold larger than the UK. The USA’s economy is about 8 times larger than the UK, but this remains a massive gap.

A country that the UK would more commonly compare itself, both in the overall size of its economy and the importance it attaches to defence, is France. France spent €5.6 bn on defence R&D in 2020, more than four times the UK figure, despite roughly comparable overall expenditures on defence.

Definitions of the boundary between R&D and deployment make comparisons difficult, but it’s tempting to interpret this as a consequence of France’s traditionally more Gaullist approach to defence, preferring to develop its own systems rather than relying on allies. In an increasingly uncertain world, it’s going to be important to get this balance right.

6.3. Department of Health and Social Care

As defence R&D was run down, the relative beneficiary was research for health and life sciences. One big institutional manifestation of this shift was the foundation in 2006 of the National Institute of Health Research, to bring together R&D funded directly through the Department of Health in association with NHS England. This remains distinct from the Medical Research Council, which is now incorporated in UK Research and Innovation; NIHR’s focus on England means that the devolved nations have their own budgets. For health research. NIHR is now a major component of the public R&D system – in 19/20 it spent £1.1 bn on research, infrastructure and research training, accounting for about 90% of DHSC’s research spend.

The mission of NIHR is “to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research.” This statement neatly encapsulates the twin goals of the UK’s overall Life Sciences strategy, to improve the delivery of health and social care to the nation’s citizens, on the one hand, and to support the pharma, biotech and medical technology sectors on the other. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, these goals are often not sufficiently differentiated, meaning that the potential tensions between them are not resolved. In my view, NIHR’s close relationship with the National Health Service should mean that NIHR’s focus should remain on improving the health outcomes of the UK’s citizens, with the support of any commercial opportunities that flow from this a secondary goal.

Health R&D was a big beneficiary of the 2021 Spending Review, and if NIHR’s budget rises in line with the overall DHSC R&D budget, this should bring a £730m uplift in NIHR funding compared to flat cash.

One issue that could be addressed in the context of this overall funding uplift is the geographical concentration of NIHR research, which historically has been even more focused on the Golden Triangle (and, within that, on London in particular) than research council funding. In 2018, around 52% of NIHR funding went to London and the Southeast, with 35% of that in London, whose share of England’s population is 16% (Source: UK Health Research Analysis).

NIHR has a vision of a population ‘actively involved in research to improve health and wellbeing for themselves, their families and their communities’. It’s obviously impossible to deliver this vision with such great geographical concentration, particularly given the mismatch between the parts of the country with the worst health outcomes and the geographical location of much of NIHR’s research.

It’s good, therefore, to see in NIHR’s latest strategy document Best Research for Best Health: The Next Chapter, recognition that ‘people in regions and communities where the burden of need is greatest are often under-served by research’, and a commitment to ‘Bringing clinical and applied research to under-served regions and communities with major health needs’.

To achieve this will require the development of research capacity outside the Golden Triangle. It’s good, therefore, to see a commitment to ‘nurture new NHS and non-NHS research sites located in regions that have high health and social care needs and have historically been less active in research, introducing new initiatives to enhance their capacity and capabilities.’

It’s important that NIHR follows through on these welcome commitments; the UK’s health inequalities are, in my view, unacceptable in principle, but also a serious drag on the productivity of those regions where health outcomes are worst. The strengthening of existing and emerging clusters of life sciences and health technology industries outside the Greater Southeast will be an additional benefit.

6.4. Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (excluding UKRI)

BEIS has the largest R&D budget of all departments, but this is because it is the official department sponsor for UK Research and Innovation, which I discussed in part 5 of this series. Nonetheless, it does have a significant R&D budget of its own, outside UKRI. In 2020, this amounted to just over £1 billion.

In part, this is used to support some important remaining components of state R&D infrastructure. The National Physical Laboratory is responsible for the standards and metrology that underpin commerce and industry, for example maintaining the national system for measuring and defining time accurately. The Met Office produces increasingly accurate weather forecasts, relying on the processing of massive amounts of data and high performance computing, and is increasingly concerned with modelling the effects of climate change. The UK Atomic Energy Authority, much shrunk in scale since the 1980s, is now exclusively concerned with research to develop nuclear fusion as a source of electricity. UKAEA is one of the few remaining parts of civil government that retains the capacity to undertake large scale, complex engineering projects at the frontiers of technology.

As its name suggests, BEIS is responsible for applied R&D in support of industrial strategy. Following the 2017 White Paper, the government established “sector deals” in support of specific sectors, often involving R&D programmes jointly funded by government and industry. The Aerospace sector deal is possibly the most mature, with the Aerospace Technology Institute established as the vehicle for that joint research programme. The future of the “sector deal” approach seems to be in doubt now; the 2017 Industrial Strategy was superseded in 2021 by a new, HM Treasury driven, Plan for Growth, which turned away from so-called “vertical” strategy focused on specific sectors. (discussed in my blogpost “What next for Industrial Strategy”).

BEIS took over responsibility for energy and climate change in 2016, when the formerly free standing Department of Energy and Climate Change was amalgamated with the department. Thus it inherited the DECC R&D budget, which at that time stood at £47 m. Given the scale of the challenge of moving to net zero, and the need for innovation to make what will be a wrenching economic transition affordable, this seems a small level of funding.

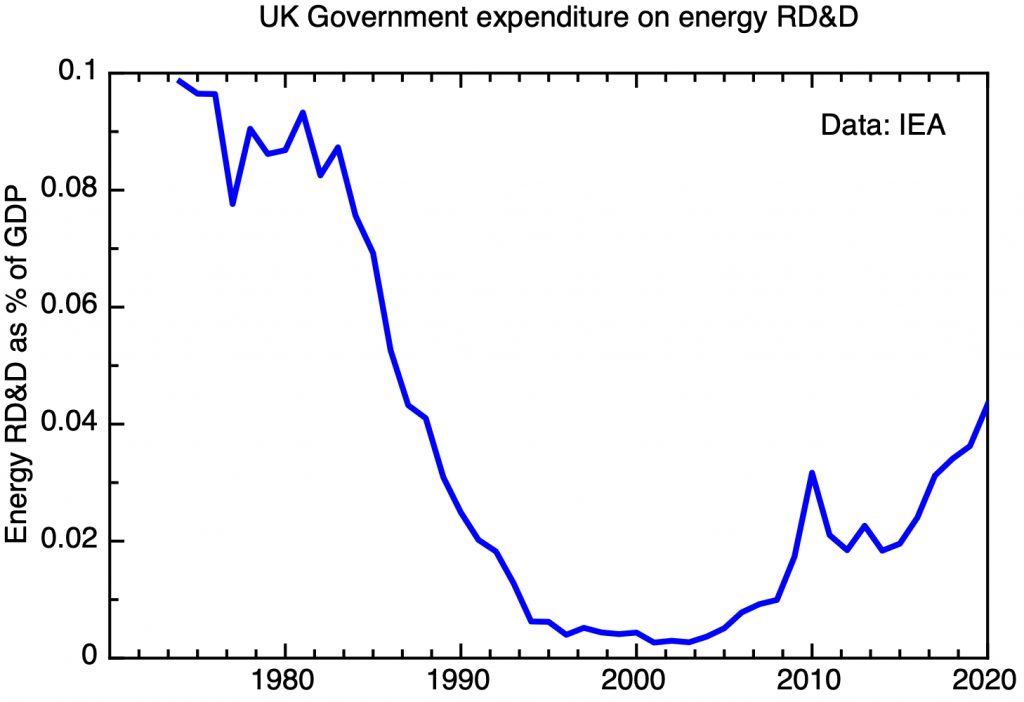

It’s worth stressing just how low the UK government’s spending on energy research fell in the 1990s. The low point, of just £30m, was in 2001. The scale of the collapse in state spending is made clear in my plot, which shows total government spending Research, development and demonstration as a fraction of GDP. The reasons for this fall are explored in an earlier post of mine, We sold out our energy future. In short, I suspect it arose from a combination of the complacency that arose from having discovered a large supply of oil and gas, and an ideological conviction that energy supply could and should be entirely left to the market.

UK government spending on energy research, development and demonstration as a faction of GDP. Data: International Energy Agency.

These totals include the UK Atomic Energy Authority’s spending on fusion research, together with more upstream research funded by the research councils (mainly EPSRC). It’s good that they are increasing again; the government now has a Net Zero Research and Innovation Framework

and a Net Zero Innovation Portfolio supporting the UK Government’s “Ten point plan for a green industrial revolution” (see my earlier blogpost for a more detailed analysis of this)

We’ll see how this plan develops.

Up next…

In the next (and, I hope, penultimate) part of this series, I’ll look at the EU Horizon programme (and what might replace it), and the new agency ARIA.

In the past, the UK government has funded R&D indirectly through the EU Horizon programme. Following Brexit, this is in question, despite the UK government’s stated desire to associate with Horizon in the future. I’ll discuss the distinctive roles of EU funding, and what might replace it in the increasingly likely scenario that the UK is not able to associate. Finally, I’ll mention the new agency ARIA (the Advanced Research and Innovation Agency), with some early thoughts about the role this might play in the overall system.

the forthcoming EU analysis will be intriguing. who do you think is blocking UK/Swiss association within the EU? A lot of the EPP voices you hear in Bxl argue in favor of association regardless of politics but their words seems to bounce off DG R&I.