My article on the UK’s productivity slowdown has now been published as a Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute Paper, and is available for download here. Here is its introduction/summary:

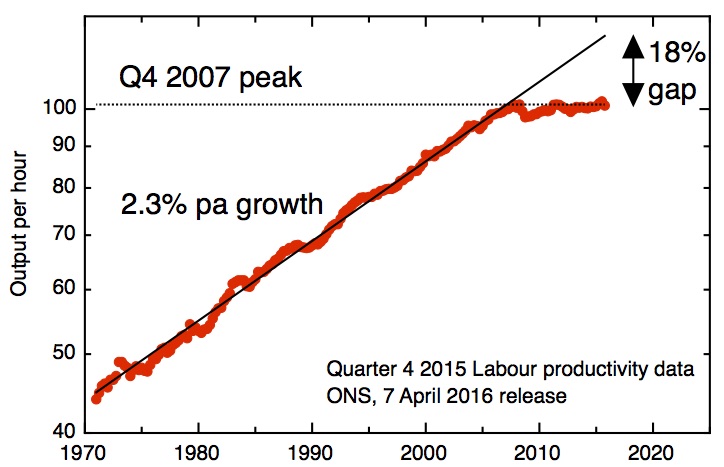

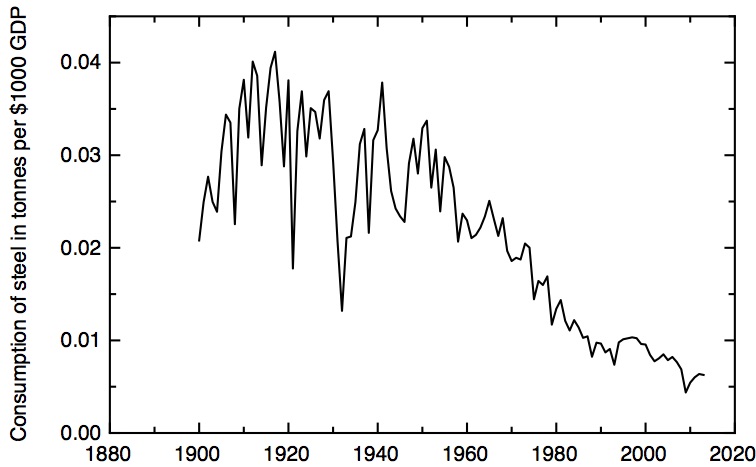

The UK is in the midst of an unprecedented peacetime slowdown in productivity growth, which comes on top of the nation’s long-standing productivity weakness compared to the USA, France and Germany. If this trend continues, UK living standards will continue to stagnate and the government’s ambition to eliminate the deficit will fail. Productivity growth is connected with innovation, in its broadest sense, so it is natural to explore the connection between the UK’s poor productivity performance and the low R&D intensity of its economy. More careful analyses of productivity look at the performance of individual sectors and allow some more detailed explanations of the productivity slowdown to be tested. The decline of North Sea oil and gas and the end of the financial services bubble have a special role in the UK’s poor recent performance; these do not explain all the problem, but they will provide a headwind that the economy will have to overcome over the coming years. In response, the UK government will need to take a more active role in procuring and driving technological innovation, particularly in areas where such innovation is needed to meet the strategic goals of the state. We need a new political economy of technological innovation.