We are currently waiting for the UK government to publish its semiconductor strategy. As context for such a strategy, my previous two blogposts have summarised the global state of the industry:

Part 1: the UK’s place in the semiconductor world

Part 2: the past and future of the global semiconductor industry

Here I consider what a realistic and useful UK semiconductor strategy might include.

To summarise the global context, the essential nations in advanced semiconductor manufacturing are Taiwan, Korea and the USA for making the chips themselves. In addition, Japan and the Netherlands are vital for crucial elements of the supply chain, particularly the equipment needed to make chips. China has been devoting significant resource to develop its own semiconductor industry – as a result, it is strong in all but the most advanced technologies for chip manufacture, but is vulnerable to being cut off from crucial elements of the supply chain.

The technology of chip manufacture is approaching maturity; the very rapid rates of increase in computing power we saw in the 1980s and 1990s, associated with a combination of Moore’s law and Dennard scaling, have significantly slowed. At the technology frontier we are seeing diminishing returns from the ever larger investments in capital and R&D that are needed to maintain advances. Further improvements in computer performance are likely to put more premium on custom designs for chips optimised for specific applications.

The UK’s position in semiconductor manufacturing is marginal in a global perspective, and not a relative strength in the context of the overall UK economy. There is actually a slightly stronger position in the wider supply chain than in chip manufacture itself, but the most significant strength is not in manufacture, but design, with ARM having a globally significant position and newcomers like Graphcore showing promise.

The history of the global semiconductor industry is a history of major government interventions coupled with very large private sector R&D spending, the latter driven by dramatically increasing sales. The UK essentially opted out of the race in the 1980’s, since when Korea and Taiwan have established globally leading positions, and China has become a fast expanding new entrant to the industry.

The more difficult geopolitical environment has led to a return of industrial strategy on a huge scale, led by the USA’s CHIPS Act, which appropriates more than $50 billion over 5 years to reestablish its global leadership, including $39 billion on direct subsidies for manufacturing.

How should the UK respond? What I’m talking about here is the core business of manufacturing semiconductor devices and the surrounding supply chain, rather than information and communication technology more widely. First, though, let’s be clear about what the goals of a UK semiconductor strategy could be.

What is a semiconductor strategy for?

A national strategy for semiconductors could have multiple goals. The UK Science and Technology Framework identifies semiconductors as one of five critical technologies, judged against criteria including their foundational character, market potential, as well as their importance for other national priorities, including national security.

It might be helpful to distinguish two slightly different goals for the semiconductor strategy. The first is the question of security, in the broadest sense, prompted by the supply problems that emerged in the pandemic, and heightened by the growing realisation of the importance and vulnerability of Taiwan in the global semiconductor industry. Here the questions to ask are, what industries are at risk from further disruptions? What are the national security issues that would arise from interruptions in supply?

The government’s latest refresh of its integrated foreign and defence strategy promises to “ensure the UK has a clear route to assured access for each [critical technology], a strong voice in influencing their development and use internationally, a managed approach to supply chain risks, and a plan to protect our advantage as we build it.” It reasserts as a model introduced in the previous Integrated Review the “own, collaborate, access” framework.

This framework is a welcome recognition of the the fact that the UK is a medium size country which can’t do everything, and in order to have access to the technology it needs, it must in some cases collaborate with friendly nations, and in others access technology through open global markets. But it’s worth asking what exactly is meant by “own”. This is defined in the Integrated Review thus: “Own: where the UK has leadership and ownership of new developments, from discovery to large-scale manufacture and commercialisation.”

In what sense does the nation ever own a technology? There are still a few cases where wholly state owned organisations retain both a practical and legal monopoly on a particular technology – nuclear weapons remain the most obvious example. But technologies are largely controlled by private sector companies with a complex, and often global ownership structure. We might think that the technologies of semiconductor integrated circuit design that ARM developed are British, because the company is based in Cambridge. But it’s owned by a Japanese investment bank, who have a great deal of latitude in what they do with it.

Perhaps it is more helpful to talk about control than ownership. The UK state retains a certain amount of control of technologies owned by companies with a substantial UK presence – it has been able in effect to block the purchase of the Newport Wafer Fab by the Chinese owned company Nexperia. But this new assertiveness is a very recent phenomenon; until very recently UK governments have been entirely relaxed about the acquisition of technology companies by overseas companies. Indeed, in 2016 ARM’s acquisition by Softbank was welcomed by the then PM, Theresa May, as being in the UK’s national interest, and a vote of confidence in post-Brexit Britain. The government has taken new powers to block acquisitions of companies through the National Security and Investment Act 2021, but this can only be done on grounds of national security.

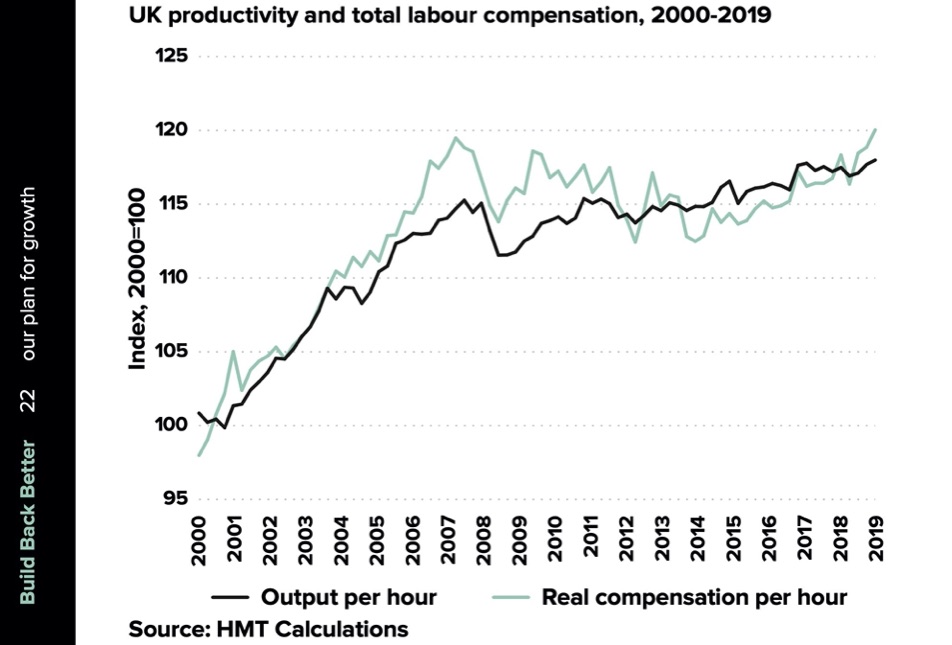

The second goal of a semiconductor strategy is as part of an effort to overcome the UK’s persistent stagnation of economic productivity, to “generate innovation-led economic growth” , in the words of a recent Government response to a BEIS Select Committee report. As I have written about at length, the UK’s productivity problem is serious and persistent, so there’s certainly a need to identify and support high value sectors with the potential for growth. There is a regional dimension here, recognised in the government’s aspiration for the strategy to create “high paying jobs throughout the UK”. So it would be entirely appropriate for a strategy to support the existing cluster in the Southwest around Bristol and into South Wales, as well as to create new clusters where there are strengths in related industry sectors

The economies of Taiwan and Korea have been transformed by their very effective deployment of an active industrial strategy to take advantage of an industry at a time of rapid technological progress and expanding markets. There are two questions for the UK now. Has the UK state (and the wider economic consensus in the country) overcome its ideological aversion to active industrial strategy on the East Asian model to intervene at the necessary scale? And, would such an intervention be timely, given where semiconductors are in the technology cycle? Or, to put it more provocatively, has the UK left it too late to capture a significant share of a technology that is approaching maturity?

What, realistically, can the UK do about semiconductors?

What interventions are possible for the UK government in devising a semiconductor strategy that addresses these two goals – of increasing the UK’s economic and military security by reducing its vulnerability to shocks in the global semiconductor supply chain, and of improving the UK’s economic performance by driving innovation-led economic growth? There is a menu of options, and what the government chooses will depend on its appetite for spending money, its willingness to take assets onto its balance sheet, and how much it is prepared to intervene in the market.

Could the UK establish the manufacturing of leading edge silicon chips? This seems implausible. This is the most sophisticated manufacturing process in the world, enormously capital intensive and drawing on a huge amount of proprietary and tacit knowledge. The only way it could happen is if one of the three companies currently at or close to the technology frontier – Samsung, Intel or TSMC – could be enticed to establish a manufacturing plant in the UK. What would be in it for them? The UK doesn’t have a big market, it has a labour market that is high cost, yet lacking in the necessary skills, so its only chance would be to advance large direct subsidies.

In any case, the attention of these companies is elsewhere. TSMC is building a new plant in Arizona, at a cost of $40 billion, while Samsung’s new plant in Texas is costing $25 billion, with the US government using some of the CHIPS act money to subsidise these investments. Despite Intel’s well-reported difficulties, it is planning significant investment in Europe, supported by inducements from EU and its member states under the EU Chips act. Intel has committed €12 billion to expanding its operations in Ireland and €17 billion for a new fab in the existing semiconductor cluster in Saxony, Germany.

From the point of view of security of supply, it’s not just chips from the leading edge that are important; for many applications, in automobiles, defence and industrial machinery, legacy chips produced by processes that are no longer at the leading edge are sufficient. In principle establishing manufacturing facilities for such legacy chips would be less challenging than attempting to establish manufacturing at the leading edge. However, here, the economics of establishing new manufacturing facilities is very difficult. The cost of producing chips is dominated by the need to amortise the very large capital cost of setting up a fab, but a new plant would be in competition with long-established plants whose capital cost is already fully depreciated. These legacy chips are a commodity product.

So in practise, our security of supply can only be assured by reliance on friendly countries. It would have been helpful if the UK had been able to participate in the development of a European strategy to secure semiconductor supply chains, as Hermann Hauser has argued for. But what does the UK have to contribute, in the creation of more resilient supply chains more localised in networks of reliably friendly countries?

The UK’s key asset is its position in chip design, with ARM as the anchor firm. But, as a firm based on intellectual property rather than the big capital investments of fabs and factories, ARM is potentially footloose, and as we’ve seen, it isn’t British by ownership. Rather it is owned and controlled by a Japanese conglomerate, which needs to sell it to raise money, and will seek to achieve the highest return from such a sale. After the proposed sale to Nvidia was blocked, the likely outcome now is a floatation on the US stock market, where the typical valuations of tech companies are higher than they are in the UK.

The UK state could seek to maintain control over ARM by the device of a “Golden Share”, as it currently does with Rolls-Royce and BAE Systems. I’m not sure what the mechanism for this would be – I would imagine that the only surefire way of doing this would be for the UK government to buy ARM outright from Softbank in an agreed sale, and then subsequently float it itself with the golden share in place. I don’t suppose this would be cheap – the agreed price for the thwarted Nvidia take over was $66 billion. The UK government would then attempt to recoup as much of the purchase price as possible through a subsequent floatation, but the presence of the golden share would presumably reduce the market value of the remaining shares. Still, the UK government did spend £46 billion nationalising a bank.

What other levers does the UK have to consolidate its position in chip design? Intelligent use of government purchasing power is often cited as an ingredient of a successful industrial policy, and here there is an opportunity. The government made the welcome announcement in the Spring Budget that it would commit £900 m to build an exascale computer to create a sovereign capability in artificial intelligence. The procurement process for this facility should be designed to drive innovation in the design, by UK companies, of specialised processing units for AI with lower energy consumption.

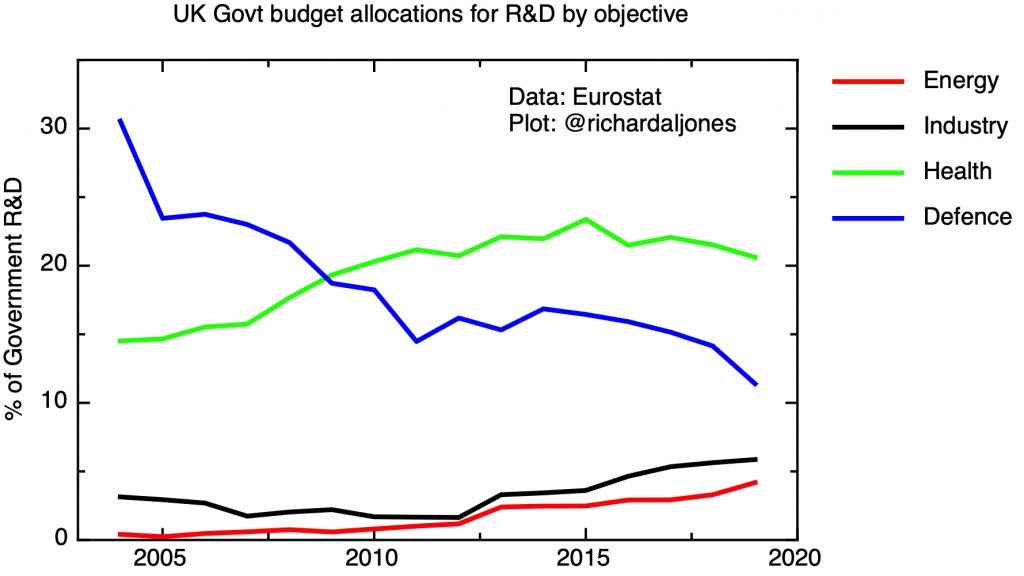

A strong public R&D base is a necessary – but not sufficient – condition for an effective industrial strategy in any R&D intensive industry. As a matter of policy, the UK ran down its public sector research effort in mainstream silicon microelectronics, in response to the UK’s overall weak position in the industry. The Engineering and Physical Research Council announces on its website that: “In 2011, EPSRC decided not to support research aimed at miniaturisation of CMOS devices through gate-length reduction, as large non-UK industrial investment in this field meant such research would have been unlikely to have had significant national impact.” I don’t think this was – or is – an unreasonable policy given the realities of the UK’s global position. The UK maintains academic research strength in areas such III-V semiconductors for optoelectronics, 2-d materials such as graphene, and organic semiconductors, to give a few examples.

Given the sophistication of state of the art microelectronic manufacturing technology, for R&D to be relevant and translatable into commercial products it is important that open access facilities are available to allow the prototyping of research devices, and with pilot scale equipment to demonstrate manufacturability and facilitate scale-up. The UK doesn’t have research centres on the scale of Belgium’s IMEC, or Taiwan’s ITRI, and the issue is whether, given the shallowness of the UK’s industry base, there would be a customer base for such a facility. There are a number of university facilities focused on supporting academic researchers in various specialisms – at Glasgow, Manchester, Sheffield and Cambridge, to give some examples. Two centres are associated with the Catapult Network – The National Printable Electronics Centre in Sedgefield, and the Compound Semiconductor Catapult in South Wales.

This existing infrastructure is certainly insufficient to support an ambition to expand the UK’s semiconductor sector. But a decision to enhance this research infrastructure will need a careful and realistic evaluation of what niches the UK could realistically hope to build some presence in, building on areas of existing UK strength, and understanding the scale of investment elsewhere in the world.

To summarise, the UK must recognise that, in semiconductors, it is currently in a relatively weak position. For security of supply, the focus must be on staying close to like-minded countries like our European neighbours. For the UK to develop its own semiconductor industry further, the emphasis must be on finding and developing particular niches where the UK’s does have some existing strength to build on, and there is the prospect of rapidly growing markets. And the UK should look after its one genuine area of strength, in chip design.

Four lessons for industrial strategy

What should the UK do about semiconductors? Another tempting, but unhelpful, answer is “I wouldn’t start from here”. The UK’s current position reflects past choices, so to conclude, perhaps it’s worth drawing some more general lessons about industrial strategy from the history of semiconductors in the UK, and globally.

1. Basic research is not enough

The historian David Edgerton has observed that it is a long-running habit of the UK state to use research policy as a substitute for industrial strategy. Basic research is relatively cheap, compared to the expensive and time-consuming process of developing and implementing new products and processes. In the 1980’s, it became conventional wisdom that governments should not get involved in applied research and development, which should be left to private industry, and, as I recently discussed at length, this has profoundly shaped the UK’s research and development landscape. But excellence in basic research has not produced a competitive semiconductor industry.

The last significant act of government support for the semiconductor industry in the UK was the Alvey programme of the 1980s. The programme was not without some technical successes, but it clearly failed in its strategic goal of keeping the UK semiconductor industry globally competitive. As the official evaluation of the programme concluded in 1991 [1]: “Support for pre-competitive R&D is a necessary but insufficient means for enhancing the competitive performance of the IT industry. The programme was not funded or equipped to deal with the different phases of the innovation process capable of being addressed by government technology policies. If enhanced competitiveness is the goal, either the funding or scope of action should be commensurate, or expectations should be lowered accordingly”.

But the right R&D institutions can be useful; the experience of both Japan and the USA shows the value of industry consortia – but this only works if there is already a strong, R&D intensive industry base. The creation of TSMC shows that it is possible to create a global giant from scratch, and this emphasises the role of translational research centres, like Taiwan’s ITRI and Belgium’s IMEC. But to be effective in creating new businesses, such centres need to have a focus on process improvement and manufacturing, as well as discovery science.

2. Big is beautiful in deep tech.

The modern semiconductor industry is the epitome of “Deep Tech”: hard innovation, usually in the material or biological domains, demanding long term R&D efforts and large capital investments. For all the romance of garage-based start-ups, in a business that demands up-front capital investments in the $10’s of billions and annual research budgets on the scale of medium size nation states, one needs serious, large scale organisations to succeed.

The ownership and control of these organisations does matter. From a national point of view, it is important to have large firms anchored to the territory, whether by ownership or by significant capital investment that would be hard to undo, so ensuring the permanence of such firms is the legitimate business of government. Naturally, big firms often start as fast growing small ones, and the UK should make more effort to hang on to companies as they scale up.

3. Getting the timing right in the technology cycle

Technological progress is uneven – at any given time, one industry may be undergoing very dramatic technological change, while other sectors are relatively stagnant. There may be a moment when the state of technology promises a period of rapid development, and there is a matching market with the potential for fast growth. Firms that have the capacity to invest and exploit such “windows of opportunity”, to use David Sainsbury’s phrase, will be able to generate and capture a high and rising level of added value.

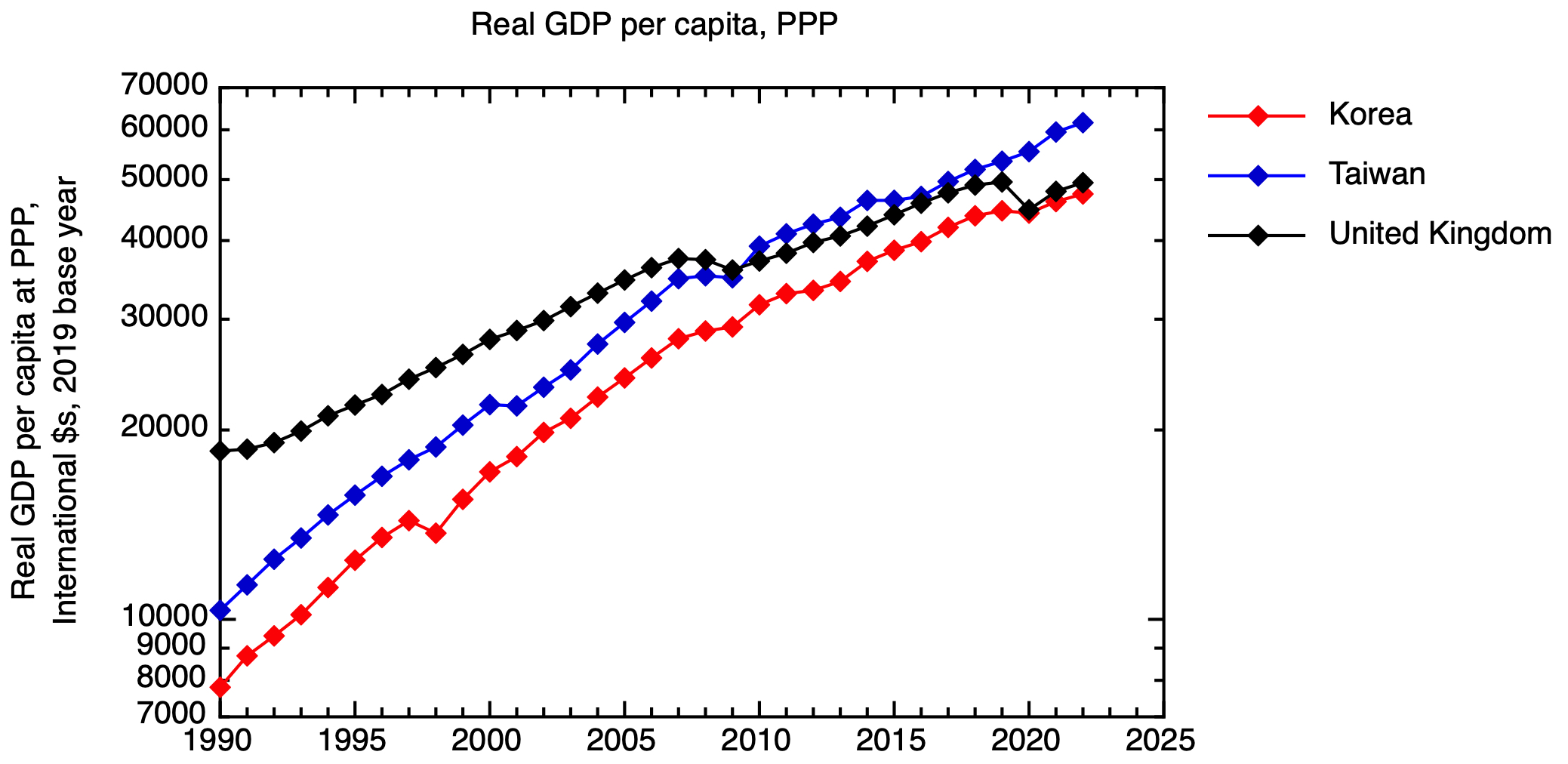

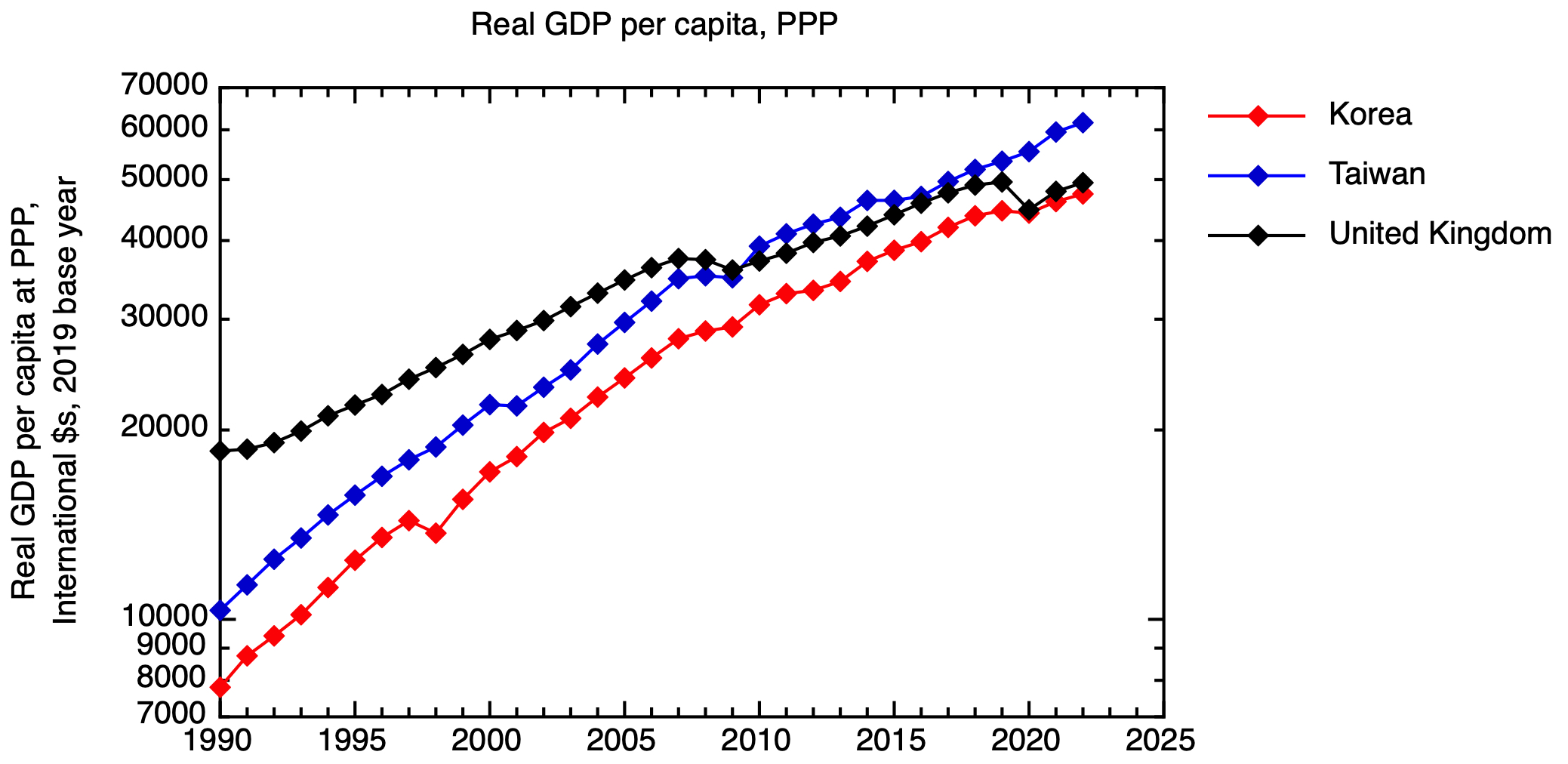

The timing of interventions to support such firms is crucial, and undoubtedly not easy, but history shows us that nations that are able to offer significant levels of strategic support at the right stage can see a material impact on their economic performance. The recent rapid economic growth of Korea and Taiwan is a case in point. These countries have gone beyond catch-up economic growth, to equal or surpass the UK, reflecting their reaching the technological frontier in high value sectors such as semiconductors. Of course, in these countries, there has been a much closer entanglement between the state and firms than UK policy makers are comfortable with.

Real GDP per capita at purchasing power parity for Taiwan, Korea and the UK. Based on data from the IMF. GDP at PPP in international dollars was taken for the base year of 2019, and a time series constructed using IMF real GDP growth data, & then expressed per capita.

4. If you don’t choose sectors, sectors will choose you

In the UK, so-called “vertical” industrial strategy, where explicit choices are made to support specific sectors, have long been out of favour. Making choices between sectors is difficult, and being perceived to have made the wrong choices damages the reputation of individuals and institutions. But even in the absence of an explicitly articulated vertical industrial strategy, policy choices will have the effect of favouring one sector over another.

In the 1990s and 2000s, UK chose oil and gas and financial services over semiconductors, or indeed advanced manufacturing more generally. Our current economic situation reflects, in part, that choice.

[1] Evaluation of the Alvey Programme for Advanced Information Technology. Ken Guy, Luke Georghiou, et al. HMSO for DTI and SERC (1991)